THE CASES

Winston S* is a 23-year-old man referred by a psychiatrist colleague for primary care. He works delivering papers in the early morning hours and spends his day alone in his apartment mainly eating frozen pizza. He has worked solitary jobs his entire life and says he prefers it that way. His answers to questions lack emotion. He doesn’t seem to have any friends or regular contact with family. He follows the medical advice he receives but can’t seem to get out of the house to exercise or socialize. His psychiatrist was treating him with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor for depression when he was referred.

Denise L* is a 37-year-old woman who transferred to your practice because she says the previous practice’s office manager was disrespectful and the doctor did not listen to her. She has been “very appreciative” of you and your “well-run office.” You have addressed her fibromyalgia and she has shared several personal details about her life. In the following weeks, you receive several phone calls and messages from her. At a follow-up visit, she asks questions about your family and seems agitated when you hesitate to answer. She questions whether you remember details of her history. She pushes, “Did you remember that, doctor?” She also mentions that your front desk staff seems rude to her.

Ruth B* is an 82-year-old woman whose blood pressure measured in your office is 176/94 mm Hg. When you recommend starting a medication and getting blood tests, she responds with a litany of fearful questions. She seems immobilized by worries about treatment and equally so about the risks of nontreatment. You can’t seem to get past the anxiety to decide on a satisfactory plan. She has to write everything down on a notepad and worries if she does not get every detail.

● How would you proceed with these patients?

* This patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity. The other 2 patients are an amalgam of patients for whom the authors have provided care.

According to a survey of practicing primary care physicians, as many as 15% of patient encounters can be difficult.1 Demanding, intrusive, or angry patients who reject health care interventions are often-cited sources of these difficulties.2,3 While it is true that patient, physician, and environmental factors may contribute to challenging interactions, some patients who are “difficult” may actually have a personality disorder that requires a distinctive approach to care. Recognizing these patients can help empower physicians to provide compassionate and effective care, reduce team angst, and minimize burnout.

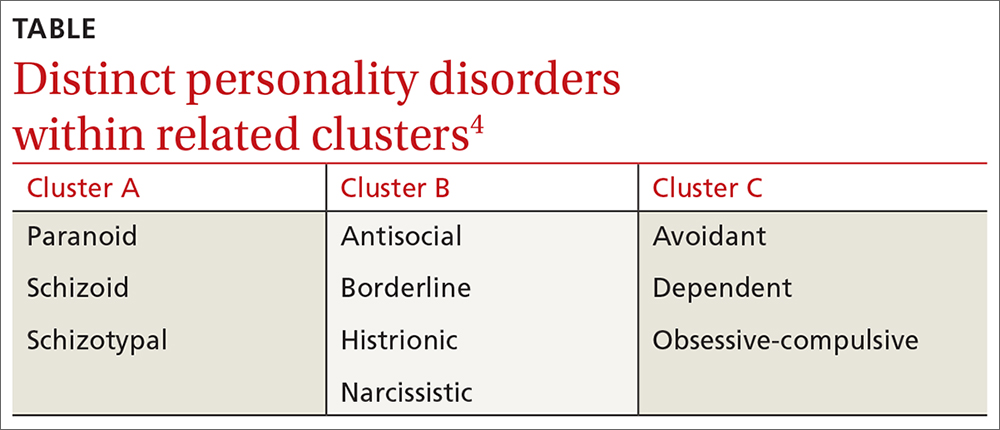

❚ What qualifies as a personality disorder? A personality disorder is an enduring pattern of inner experience and behavior that deviates markedly from the expectations of the individual’s culture, is pervasive and inflexible, has an onset in adolescence or early adulthood, is unchanging over time, and leads to distress or impairment in social or occupational functioning.4 The prevalence of any personality disorder seems to have increased over the past decade from 9.1%4 to 12.16%.5 The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) classifies personality disorders in 3 clusters—A, B, and C (TABLE4)—with prevalence rates at 7.23%, 5.53%, and 6.7%, respectively.5 The review below will focus on the distinct personality disorders exhibited by the patients described in the opening cases.

Continue to: A closer look at the clusters...