Osteoarthritic (OA) knees with varus deformities commonly present with tight, contracted medial collateral ligaments and soft-tissue sleeves.1 More severe varus deformities require more extensive medial releases on the concave side to optimize flexion-extension gaps. Excessive soft-tissue releases in milder varus deformities can result in medial instability in flexion and extension.2-4 Misjudgments in soft-tissue release can therefore lead to knee instability, an important cause of early total knee arthroplasty (TKA) failures.2,5,6 Some authors have reported difficulty in coronal plane balancing in knees with preoperative varus deformity of more than 20°.4,7

Surgeons often refer to varus as a description of coronal malalignment, mainly with the knee in extension. In the surgical setting, however, descriptions are given regarding differential medial soft-tissue tightness in extension and flexion. Balancing the knee in extension may not necessarily balance the knee in flexion. Thus, there is the concept of extension and flexion varus, which has not been well described in the literature. Releases on the anterior medial and posterior medial aspects of the proximal tibia have differential effects on flexion and extension gaps, respectively.2

Intraoperative alignment certainly has a pivotal role in component longevity.8 Since its advent in the 1990s, use of computer navigation in TKA has offered new hope for improving component alignment. Some authors routinely use computer navigation for intraoperative soft-tissue releases.9 A recent meta-analysis found that computer-navigated surgery is associated with fewer outliers in final component alignment compared with conventional TKA.10

Increased use of computer navigation in TKA at our institution in recent years has come with the observation that knees with severe extension varus seem to have correspondingly more severe flexion varus. Before computer navigation, coronal alignment of knees in flexion was almost impossible to measure because of the spatial alignment of the knees in that position.

We conducted a study to evaluate the relationship of extension and flexion varus in OA knees and to determine whether severity of fixed flexion deformity (FFD) in the sagittal plane correlates with severity of coronal plane varus deformity. We hypothesized that there would be differential varus in flexion and extension and that increasing knee extension varus would correlate closely with knee flexion varus beyond a certain tibiofemoral angle. We also hypothesized that severity of sagittal plane deformity will correlate with the severity of coronal plane deformity.

Patients and Methods

Data Collection

After this study was approved by our institution’s ethics review committee, we prospectively collected data from 403 consecutive computer-navigated TKAs performed at our institution between November 2008 and August 2011. Dr. Tan, who was not the primary physician, retrospectively analyzed the radiographic and navigation data.

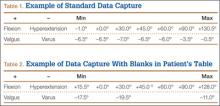

Each patient’s knee varus-valgus angles were captured by Dr. Teo, an adult reconstruction surgeon, in standard fashion from maximal extension to 0º, 30º, 45º, 60º, 90º, and maximal flexion. An example of standard data capture appears in Table 1. With varus-hyperextension defined as –0.5° or less (more negative), neutral as 0°, and valgus-flexion as 0.5° or more, there were 362 varus knees, 41 valgus knees, and no neutral knees.

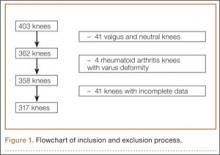

Study inclusion criteria were OA and varus deformity. Exclusion criteria were rheumatoid arthritis, other types of inflammatory arthritis, neuromuscular disorders, knees with valgus angulation, and incomplete data (Table 2). Figure 1 summarizes the inclusion/exclusion process, which left 317 knees available for study. Cases of incomplete data were likely due to computer errors or to inadvertent movement when navigation data were being acquired during surgery.

In conventional TKA, the main objective is to equalize flexion-extension gaps with knee at 90° flexion and 0° extension. The ability to achieve this often implies the knee will be balanced throughout its range of motion (ROM). From the data for the 317 study knees, 3 sets of values were extracted: varus angles from maximal knee extension (extension varus), varus angles from 90° knee flexion (flexion varus), and maximal knee extension. All knees were able to achieve 90° flexion.

Power Calculation

Our analysis used a correlation coefficient (r) of at least 0.5 at a 5% level of significance and power of 80%. With 317 knees, the study was more than adequately powered for significance.

Surgical and Navigation Technique

All patients underwent either general or regional anesthesia for their surgeries, which were performed by Dr. Teo. Standard medial parapatellar arthrotomy was performed. Navigation pins were then inserted into the femur and tibia outside the knee wound. Anatomical reference points were digitized per routine navigation requirements. (The reference for varus-valgus alignment of the femur is the mechanical femur axis defined by the digitized hip center and knee center, and the reference for varus-valgus alignment of the tibia is the mechanical tibia axis defined by the digitized tibia center and calculated ankle center. The ankle center is calculated by dividing the digitized transmalleolar axis according to a ratio of 56% lateral to 44% medial with the inherent navigation software.) Our institution uses an imageless navigation system (Navigation System II; Stryker Orthopedics, Mahwah, New Jersey).