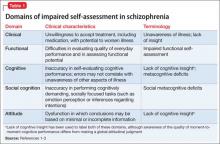

Lack of insight or “unawareness of illness” occurs within a set of self-assessment problems commonly seen in schizophrenia.1 In the clinical domain, people who do not realize they are ill typically are unwilling to accept treatment, including medication, with potential for worsened illness. They also may have difficulty self-assessing everyday function and functional potential, cognition, social cognition, and attitude, often to a variable degree across these domains (Table 1).1-3

Self-assessment of performance can be clinically helpful whether performance is objectively good or bad. Those with poor performance could be helped to attempt to match their aspirations to accomplishments and improve over time. Good performers could have their functioning bolstered by recognizing their competence. Thus, even a population whose performance often is poor could benefit from accurate self-assessment or experience additional challenges from inaccurate self-evaluation.

This article discusses patient characteristics associated with impairments in self-assessment and the most accurate sources of information for clinicians about patient functioning. Our research shows that an experienced psychiatrist is well positioned to make accurate judgments of functional potential and cognitive abilities for people with schizophrenia.

Patterns in patients with impaired self-assessment

Healthy individuals routinely overestimate their abilities and their attractiveness to others.4 Feedback that deflates these exaggerated estimates increases the accuracy of their self-assessments. Mildly depressed individuals typically are the most accurate judges of their true functioning; those with more severe levels of depression tend to underestimate their competence. Thus, simply being an inaccurate self-assessor is not “abnormal.” These response biases are consistent and predictable in healthy people.

People with severe mental illness pose a different challenge. As in the following cases, their reports manifest minimal correlation with other sources of information, including objective information about performance.

CASE 1

JR, age 28, is referred for occupational therapy because he has never worked since graduating from high school. He tells the therapist his cognitive abilities are average and intact, although his scores on a comprehensive cognitive assessment suggest performance at the first percentile of normal distribution or less. His self-reported Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) score is 4. He says he would like to work as a certified public accountant, because he believes he has an aptitude for math. He admits he has no idea what the job entails, but he is quite motivated to set up an interview as soon as possible.

CASE 2

LM, age 48, says his “best job” was managing an auto parts store for 18 months after he earned an associate’s degree and until his second psychotic episode. His most recent work was approximately 12 years ago at an oil-change facility. He agrees to discuss employment but feels his vocational skills are too deteriorated for him to succeed and requests an assessment for Alzheimer’s disease. His cognitive performance averages in the 10th percentile of the overall population, and his BDI score is 18. Tests of his ability to perform vocational skills suggest he is qualified for multiple jobs, including his previous technician position.

Individuals with schizophrenia who report no depression and no work history routinely overestimate their functional potential, whereas those with a history of unsuccessful vocational attempts often underestimate their functional potential. Inaccurate self-assessment can contribute to reduced functioning—in JR’s case because of unrealistic assessment of the match between skills and vocational potential, and in LM’s case because of overly pessimistic self-evaluation. For people with schizophrenia, inability to self-evaluate can have a bidirectional adverse impact on functioning: overestimation may lead to trying tasks that are too challenging, and underestimation may lead to reduced effort and motivation to take on functional tasks.

Metacognition and introspective accuracy

“Metacognition” refers to self-assessment of the quality and accuracy of performance on cognitive tests.5-7 Problem-solving tests— such as the Wisconsin Card Sorting test (WCST), in which the person being assessed needs to solve the test through performance feedback—are metacognition tests. When errors are made, the strategy in use needs to be discarded; when responses are correct, the strategy is retained. People with schizophrenia have disproportionate difficulties with the WCST, and deficits are especially salient when the test is modified to measure self-assessment of performance and ability to use feedback to change strategies.

“Introspective accuracy” is used to describe the wide-ranging self-assessment impairments in severe mental illness. Theories of metacognition implicate a broad spectrum, of which self-assessment is 1 component, whereas introspective accuracy more specifically indicates judgments of accuracy. Because self-assessment is focused on the self, and hence is introspective, this conceptualization can be applied to self-evaluations of:

• achievement in everyday functioning (“Did I complete that task well?”)

• potential for achievement in everyday functioning (“I could do that job”)

• cognitive performance (“Yes, I remembered all of those words”)

• social cognition (“He really is angry”).