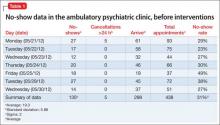

For the project, we defined no-show rate as the total number of patients who missed an appointment or canceled fewer than 24 hours before the scheduled time, divided by the total number of patients scheduled that day.

Table 1 demonstrates the no-show rate calculations for 1 of the weeks preceding the start of the project. Given approximately 800 patient appointments a month, a 31% no-show rate meant that, first, 248 patients failed to receive recommended care and, second, 248 appointment slots were wasted.

Besides undermining such components of quality care as patient safety and medication compliance, the high no-show rate also harms employee morale and productivity; impairs medical education; and, possibly, increases the use of emergency and after-hour services.

We agreed that our current no-show rate of 31% was too high.

We then formed a team of residents, faculty members, therapists, front office staff, an office manager, and an office nurse. We explored and hypothesized what could be contributing to the high no-show rate (Table 2).

Several interventions were then devised and implemented:

• Patients. We increased patient education about 1) the need for regular follow-up and 2) risks associated with medication nonadherence.

• Environment. We explored environmental limitations to access and agreed that certain static factors could not be modified—eg, location of the clinic and lack of access to public transportation. We were able to make some changes to the environment (explained later) to reduce wait time.

• Staff. Some patients had complained of long wait times, which could hinder active participation in treatment. We agreed that the clinic nurse would make rounds through the waiting room every hour and talk to patients. The nurse would identify patients who had been waiting for longer than 30 minutes after their scheduled appointment time and notify the doctor accordingly. We also agreed to revise patient appointment reminder practices: instead of using an automated answering service, one of the staff members called patients personally to remind them about their appointments. (This also allowed us to update telephone numbers for many patients; numbers on record often were outdated.) We initially recruited summer interns and provided a written script to follow during calls to patients, which allowed patients to confirm, cancel, or reschedule their appointment. Once we demonstrated positive results from the change to personal calls, the department agreed to absorb the cost, and front desk personnel began making reminder calls.

• Policies and procedures. Although some practices are able to charge a small fine for missed appointments, this was not allowed at our institution. Instead, we had several departmental policies on the books, such as discharging patients from our clinics if they missed 3 consecutive appointments and limiting prescription refills to a maximum of 6 months. These policies were neither communicated to patients and staff, nor were they implemented. We decided to educate patients and staff and implement the policies.

• Transparency. We posted the no-show rate in common areas so that the team could review and follow the progression of that rate as we implemented the changes. This allowed team members to take ownership of the project and facilitated active participation.

By implementing these changes, we aimed to reduce the no-show rate to 20%.

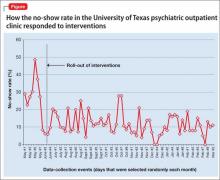

Results. We were able to reduce the no-show rate from a documented average of 31% to an average of 12% during the study period after implementing all the proposed changes in the outpatient clinics.

We calculated the no-show rate (as shown in Table 1 for May 2013), then collected the daily no-show rate from June to September 2013 (Figure). With these calculations, we demonstrated a reduction in the no-show rate to 12%. Because of the time and effort required, we reduced data collection from daily to weekly, beginning in September.

Applying the changes required consistent effort and substantial input from various stakeholders—front desk staff, residents, the nurse, therapists, and faculty. Gradually, we were able to implement all the changes.

Keeping the no-show rate low required consistent effort and monitoring of the newly implemented procedures because even a slight change, such as failure to make reminder calls, resulted in a sudden increase in the no-show rate (that was the case in October of the study period, when we were short-staffed and could not call every patient). Patients told us that it was difficult to ignore a personal call; if they were not planning to keep the appointment, the call allowed them to reschedule on the spot.

We also made sure that current no-show rates were posted in common areas, visible to team members every day.