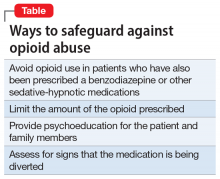

The current opioid crisis prompts additional caution in prescribing, especially when considering using short-acting, immediate-release opioids such as morphine, which have a greater potential for abuse and dependence. The Table lists safeguards that should be implemented when prescribing opioids.

Many patients with COPD in the end-of-life phase and in severe pain or discomfort due to the advanced stages of their illness receive opioids as part of palliative care. Patients with COPD whose medical care is predominantly palliative may benefit greatly from being prescribed opioids. Most patients with COPD who find relief from low-dose opioids usually have 6 to 12 months to live, and low-dose opioids may help them obtain the best possible quality of life.

Choosing opioids as a treatment involves the risk of physiologic dependence and opioid use disorder. For Ms. M, the potential benefits were thought to outweigh such risks.

OUTCOME Breathlessness improves, anxiety decreases

Ms. M’s lorazepam is discontinued, and immediate-release morphine is prescribed at a low dose of 1 mg/d on an as-needed basis for anxiety with good effect. Ms. M’s breathlessness improves, leading to an overall decrease in anxiety. She does not experience sedation, confusion, or adverse respiratory effects.

Ms. M’s anxiety and depression improve over the course of the hospitalization with this regimen. On hospital Day 25, she is discharged with a plan to continue duloxetine, 60 mg/d, ECT twice weekly, and low-dose morphine, 1 mg/d, as needed for anxiety. She is referred for pulmonary rehabilitation and CBT to maintain remission.

Continue to: The authors' observations