Clinical considerations

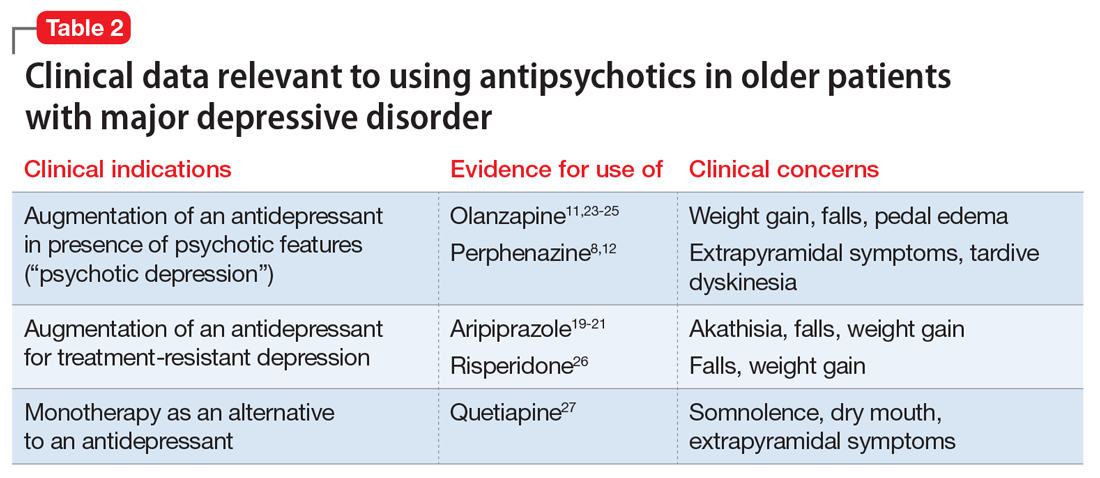

When assessing the relative benefits and risks of antipsychotics in older patients, it is important to remember that conclusions and summative opinions are necessarily influenced by the source of the data. Because much of what we know about the use of antipsychotics in geriatric adults is from clinical trials, we know more about their acute efficacy and tolerability than their long-term effectiveness and safety.28 There are similar issues regarding the role of antipsychotics in treating MDD in late life. Based on the results of several RCTs,8,11 a combination of an antidepressant plus an antipsychotic is the recommended pharmacotherapy for the acute treatment of MDD with psychotic features (Table 2).8,11,12,19-21,23-27 However, there are no published data to guide how long the antipsychotic should be continued.29

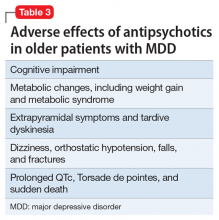

In older patients with MDD without psychotic features, 1 relatively large placebo-controlled RCT,21 2 smaller open studies,18,19 and a post hoc analysis of a large placebo-controlled RCT in mixed-age adults20 support the efficacy and relatively good tolerability of aripiprazole augmentation of an antidepressant for treatment-resistant MDD. Similarly, 1 large placebo-controlled RCT supports the efficacy and relatively good tolerability of quetiapine for non–treatment-resistant MDD. However, there are no comparative data assessing the relative merits of using these antipsychotics vs other pharmacologic strategies (eg, switching to another antidepressant, lithium augmentation, or combination of 2 antidepressants). Because older patients are more likely to experience adverse effects that may have more serious consequences (Table 3), many prudent clinicians reserve using antipsychotics as a third-line treatment in older patients with MDD without psychotic features and limit the duration of their use to a few months.30

Unfortunately, the existing literature does not provide much evidence or guidance on using antipsychotics in older people with medical comorbidity or the risks of adverse effects related to the concomitant use of other medications for chronic medical conditions. Thus, safety and tolerability data obtained from secondary analyses of mixed-age sample should be interpreted with “a grain of salt,” because the older participants included in these analyses were both relatively physically healthy and young. Individuals with acute or significant physical illness are typically excluded from many clinical trials. Based on both pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes associated with aging,5 people who are frail or age >75 should receive antipsychotic dosages that are lower (ie, between one-half to two-thirds) than typical “adult” dosages. Ideally, future research will include older adults with more extensive and generalizable medical comorbidity to inform practice recommendations.Although some data have accumulated in recent years, there are significant gaps in knowledge on the safety and tolerability of antipsychotics in older adults. The era of “big data” may provide important answers to questions such as the relative place of antipsychotics vs lithium in preserving brain health among people with bipolar disorder or treatment-resistant MDD31; whether there are true ethnic differences in terms of drugs response and adverse effect prevalence in antipsychotics32,33; or the role of pharmacogenetic evaluation in establishing individual risk–benefit ratios of antipsychotics.34