Clinical considerationsTreating OUD is challenging because of the ease with which patients can obtain opioids and because sometimes OUD occurs iatrogenically. Engaging patients in treatment is an important step in recovery, but it does not necessarily lead to reduction in opioid use. The engagement stage can involve outreach workers to encourage further treatment. Developing a therapeutic alliance and appropriately incentivizing patients also promotes entry into treatment. Motivational interviewing is used often in substance use treatment programs and can help engage patients in treatment and evaluate their willingness to change problematic behaviors.

Managing acute withdrawal symptoms. Withdrawal symptoms usually are not life threatening, but can be in the context of other medical conditions, such as autonomic instability, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and dehydration. Withdrawal symptoms also can be life-threatening during in utero exposure to a fetus. Pharmacotherapeutic options to treat opioid withdrawal symptoms include long-acting opioids, such as methadone and buprenorphine,15 which can be administered in an ambulatory setting. The combination of buprenorphine and naloxone also can be used to treat opioid withdrawal symptoms.

The alpha-2 agonist16 clonidine, although not FDA-approved for OUD or opioid withdrawal, could be used to shorten the duration of withdrawal symptoms. Clonidine also decreases methadone withdrawal and can be combined with naloxone to target naloxone-induced opioid withdrawal symptoms.17,18 Nalbuphine and butorphanol should be avoided during opioid withdrawal because they antagonize opioid receptors and can precipitate withdrawal symptoms.19,20

Maintenance phase involves long-term stabilization and relapse prevention. Treatment options include medication and non-medication interventions.21

Non-pharmacologic treatment options,22 principally psychosocial interventions, can be used on their own or in combination with medications for maintenance treatment of OUD. Psychosocial interventions include structured, professionally administered interventions such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), aversion therapy, and day-treatment programs. Interventions such as peer counseling and self-help groups also are considered psychosocial interventions, but do not require the same type of professional training.

Peer support groups such as Narcotics Anonymous (NA) help members achieve and maintain sobriety and often focus on a traditional 12-step format or on the more recent Matrix Model,23,24 which is an intensive outpatient treatment program based on components of relapse prevention, motivational interviewing, CBT, and psychoeducation.

In these peer support models, group members discuss patterns of substance use and help one another recognize and overcome problematic behaviors. Groups may vary in terms of their specific approach. For example, NA encourages group members to focus on addiction itself while Methadone Anonymous prefers participants also discuss pharmacologic treatment experiences. Additional services for finding housing and assisting with job placement are also part of some relapse prevention strategies.

Although studies on the use of abstinence-based treatments are limited, abstinence-based therapy is an option for patients wishing to undergo chemical dependency treatment without taking prescription medications to address cravings or withdrawal symptoms.25 However, abstinence-based treatments have been shown to be less effective in improving outcomes than medication-assisted treatment (MAT).26 MAT combines medications and behavioral therapies for treating substance use disorders.

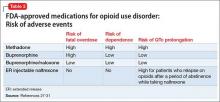

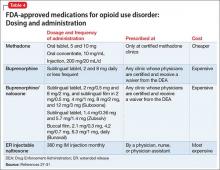

Pharmacologically, OUD can be treated with opioid agonist and antagonist medications. As summarized in Tables 2-4,27-31 these medications differ based on their pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles and intrinsic activity at mu opioid receptors. Opioid system agonists, such as methadone and buprenorphine, decrease cravings by mimicking the activity of exogenous opioids. The opioid antagonists naloxone and naltrexone reinforce abstinence by inhibiting the euphoric effects associated with opioid use. The medication of choice for a given patient depends on:

- treatment adherence

- clinical setting

- degree of withdrawal symptoms

- motivation.26

If a patient is actively seeking abstinence from opioids, either agonist or antagonist treatment can be used. In cases where a patient is not seeking abstinence, then preference should be given to opioid agonists to prevent overdose.26

Evidence suggests MAT can improve outcomes with OUD when compared with abstinence treatment alone. Several randomized, controlled, trials showed methadone and buprenorphine were more effective at treating OUD compared with treatment without medication. To date, 3 medications have been FDA-approved for treating OUD: methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone.26 All 3 medications differ in their pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles and intrinsic activities at central mu-opioid receptor, as summarized in Tables 2-4.27-31

MethadoneMethadone reduces the euphoric effects of opioid use because it binds to and blocks opioid receptors. Methadone is an opioid replacement strategy; higher dosages are used for maintenance treatment to prevent additional dosages of opioids from causing euphoria. Methadone typically is administered once daily. However, in certain circumstances, such as rapid metabolism or pregnancy, it can be given as a twice-daily dosing regimen. Specific ABCB1 variants and DRD2 genetic polymorphisms (simultaneous occurrence of ≥2 genetically determined phenotypes) might determine the dosage requirements of methadone.32