Many older patients are concerned about their memory. The “worried well” may come into your office with a list of things they can’t recall, yet they remember each “deficit” quite well. Anticipatory anxiety about one’s own decline is common, and is most often concerned with changes in memory.1,2

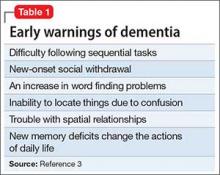

Patients with dementia or early cognitive decline often are oblivious to their cognitive changes, however. Of particular concern is progressive dementia, especially Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Although jokes about “senior moments” are common, concern about AD incurs deep-seated worry. It is essential for clinicians to differentiate normal cognitive changes of aging—particularly those in memory—from early signs of neurodegenerative disease (Table 13).

In this article, we review typical memory changes in persons age >65, and differentiate these from mild cognitive impairment (MCI), an increasingly recognized prodrome of AD. Clinicians armed with knowledge of MCI are able to reassure the worried well, or recommend neuropsychological testing as indicated.

Is memory change inevitable with aging?

Memory loss is a common problem in aging, with variable severity. Research is establishing norms in cognitive functioning through the ninth decade of life.4 Controversy about sampling, measures, and methods abound,5 and drives prolific research on the subject, which is beyond the scope of this article. It has been demonstrated that there are a few “optimally aging” persons who avoid memory decline altogether.5,6 Most researchers and clinicians agree, however, that memory change is pervasive with advancing age.

Memory change follows a gradient with recent memories lost to a greater degree than remote memories (Ribot’s Law).7 Forgetfulness is characteristic of normal aging, and frequently manifests with misplaced objects and short-term lapses. However, this is not pathological—as long as the item or memory is recalled within 24 to 48 hours.

Compared with younger adults, healthy older adults are less efficient at encoding new information. Subsequently, they have more difficulty retrieving data, particularly after a delay. The time needed to learn and use new information increases, which is referred to as processing inefficiency. This influences changes in test performance across all cognitive domains, with decreases in measures of mental processing speed, working memory, and problem-solving.

Many patients who complain about “forgetfulness” are experiencing this normal change. It is not uncommon for a patient to offer a list of things she has forgotten recently, along with the dates and circumstances in which she forgot them. Because she sometimes forgets things, but remembers them later, there likely is nothing to worry about. If reminders—such as her list—help, this too is a good sign, because it shows her resourcefulness in using accommodations. If the patient is managing her normal activities, reassurance is warranted.

Mild cognitive impairment

Since at least 1958,8 clinical observations and research have recognized a prodrome that differentiates cognitive changes predictive of dementia from those that represent typical aging. Several studies and methods have converged toward consensus that MCI is a valid construct for that purpose, with ecological validity and sound predictive value. Clinical value is evident when a patient does not meet criteria for MCI; in this case, the clinician can reassure the worried well with conviction.

Revealing the diagnosis of MCI to patients requires sensitivity and assurance that you will reevaluate the condition annually. Although there is no evidence-based remedy for MCI or means to slow its progression to dementia, data are rapidly accruing regarding the value of lifestyle changes and other nonpharmacologic interventions.9

Recognizing MCI most simply requires 2 criteria:

The patient’s expressed concern about decline in cognitive functioning from a previous level of performance. Alternately, a caretaker’s report is valuable because the patient might lack insight. You are not looking for an inability to perform activities of daily living, which is indicative of frank dementia; rather, you want to determine whether the person’s independence in functional abilities is preserved, although less efficient. Patients might repeatedly report occurrences of new problems, although modest, in some cases. Although problems with memory often are the most frequently reported symptoms, changes can be observed in any cognitive domain. Uncharacteristic inability to understand instructions, frustration with new tasks, and inflexibility are common.

Quantified clinical assessment that the patient’s cognitive decline exceeds norms of his age cohort. Clinicians are already familiar with many of these tests (5-minute recall, clock face drawing, etc.). For MCI, we recommend the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), which is specifically designed for MCI.10 It takes only 10 minutes to administer. Multiple versions of the MoCA, and instructions for its administration are available for provider use at www.mocatest.org.

When these criteria are met—a decline in previous functioning and an objective clinical confirmation—referral for neuropsychological testing is recommended. Subtypes of MCI—amnestic and non-amnestic—have been employed to specify the subtype (amnesic) that is most consistent with prodromal AD. However, this dichotomous scheme does not adequately explain or capture the heterogeneity of MCI.11,12