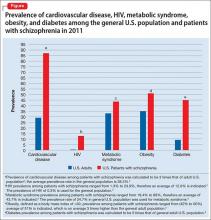

Life expectancy for both males and females has been increasing over the past several decades to an average of 76 years. However, the life expectancy among individuals with schizophrenia in the United States is 61 years—a 20% reduction.1 Patients with schizophrenia are known to be at increased risk of several comorbid medical conditions, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), coronary artery disease, and digestive and liver disorders, compared with healthy people (Figure, page 32).2-5 This risk may be heightened by several factors, including sedentary lifestyle, a high rate of cigarette use, poor self-management skills, homelessness, and poor diet.

Although substantial attention is paid to the psychiatric and behavioral management of schizophrenia, many barriers impede the detection and treatment of patients’ medical conditions, which have been implicated in excess unforeseen deaths. Patients with schizophrenia might experience delays in diagnosis, leading to more acute comorbidity at time of diagnosis and premature mortality

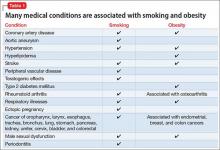

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death among psychiatric patients.6 Key risk factors for cardiovascular disease include smoking, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and lack of physical activity, all of which are more prevalent among patients with schizophrenia.7 In addition, antipsychotics are associated with adverse metabolic effects.8 In general, smoking and obesity are the most modifiable and preventable risk factors for many medical conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and many forms of cancer (Table 1).

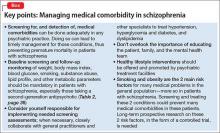

In this article, we discuss how to manage common medical comorbidities in patients with schizophrenia. Comprehensive management for all these medical conditions in this population is beyond the scope of this article; we limit ourselves to discussing (1) how common these conditions are in patients with schizophrenia compared with the general population and (2) what can be done in psychiatric practice to manage these medical comorbidities (Box).

Obesity

Obesity—defined as body mass index (BMI) of >30—is common among patients with schizophrenia. The condition leads to poor self-image, decreased treatment adherence, and an increased risk of many chronic medical conditions (Table 1). Being overweight or obese can increase stigma and social discrimination, which will undermine self-esteem and, in turn, affect adherence with medications, leading to relapse.

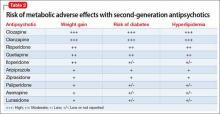

The prevalence of obesity among patients with schizophrenia is almost double that of the general population9 (Figure2-5). Several factors predispose these patients to overweight or obese, including sedentary lifestyle, lack of exercise, a high-fat diet, medications side effects, and genetic factors. Recent studies report the incidence of weight gain among patients treated with antipsychotics is as high as 80%10 (Table 2).

Mechanisms involved in antipsychotic-induced weight gain are not completely understood, but antagonism of serotonergic (5-HT2C, 5-HT1A), histamine (H1), dopamine (D2), muscarinic, and other receptors are involved in modulation of food intake. Decreased energy expenditure also has been blamed for antipsychotic-induced weight gain.10

Pharmacotherapy and bariatric surgery can be as effective among patients with schizophrenia as they are among the general population. Maintaining a BMI of <25 kg/m2 lowers the risk of cardiovascular disease by 35% to 55%.6 Metformin has modest potential for offsetting weight gain and providing some metabolic control in overweight outpatients with schizophrenia,11 and should be considered early when treating at-risk patients.

Managing obesity. Clinicians can apply several measures to manage obesity in a patient with schizophrenia:

- Educate the patient, and the family, about the risks of being overweight or obese.

- Monitor weight and BMI at each visit.

- Advise smoking cessation.

- When clinically appropriate, switch to an antipsychotic with a lower risk of weight gain—eg, from olanzapine or high-dose quetiapine to a high- or medium-potency typical antipsychotic (eg, haloperidol, perphenazine), ziprasidone, aripiprazole, iloperidone, and lurasidone (Table 2, page 36).

- Consider prophylactic use of metformin with an antipsychotic; the drug has modest potential for offsetting weight gain and providing better metabolic control in an overweight patient with schizophrenia.11

- Encourage the patient to engage in modest physical activity; for example, a 20-minute walk, every day, reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease by 35% to 55%.6

- Recommend a formal lifestyle modification program, such as behavioral group-based treatment for weight reduction.12

- Refer the patient and family to a dietitian.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

There is strong association between T2DM and schizophrenia that is related to abnormal glucose regulation independent of any adverse medication effect.13 Ryan et al14 reported that first-episode, drug-naïve patients with schizophrenia had a higher level of intra-abdominal fat than age- and BMI-matched healthy controls, suggesting that schizophrenia could be associated with changes in adiposity that might increase the risk of insulin resistance, hyperlipidemia, and dyslipidemia. Mechanisms that increase the risk of T2DM in schizophrenia include genetic and environmental factors, such as family history, lack of physical activity, and poor diet.