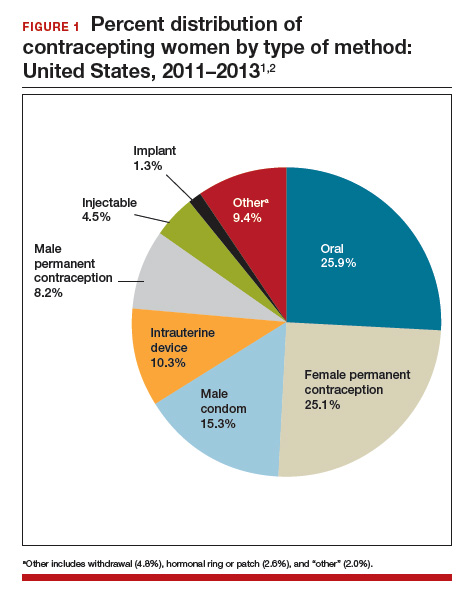

According to the most recent data (2011–2013), 62% of women of childbearing age (15–44 years) use some method of contraception. Of these “contracepting” women, about 25% reported relying on permanent contraception, making it one of the most common methods of contraception used by women in the United States (FIGURE 1).1,2 Women either can choose to have a permanent contraception procedure performed immediately postpartum, which occurs after approximately 9% of all hospital deliveries in the United States,3 or at a time separate from pregnancy.

The most common methods of permanent contraception include partial salpingectomy at the time of cesarean delivery or within 24 hours after vaginal delivery and laparoscopic occlusive procedures at a time unrelated to the postpartum period.3 Hysteroscopic occlusion of the tubal ostia is a newer option, introduced in 2002; its worldwide use is concentrated in the United States, which accounts for 80% of sales based on revenue.4

Historically, for procedures remote from pregnancy, the laparoscopic approach evolved with less sophisticated laparoscopic equipment and limited visualization, which resulted in efficiency and safety being the primary goals of the procedure.5 Accordingly, rapid occlusive procedures were commonplace. However, advancement of laparoscopic technology related to insufflation systems, surgical equipment, and video capabilities did not change this practice.

Recent literature has suggested that complete fallopian tube removal provides additional benefits. With increasing knowledge about the origin of ovarian cancer, as well as increasing data to support the hypothesis that complete tubal excision results in increased ovarian cancer protection when compared with occlusive or partial salpingectomies, both the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG)6 and the Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO)7 recommend discussing bilateral total salpingectomy with patients desiring permanent contraception. Although occlusive procedures decrease a woman’s lifetime risk of ovarian cancer by 24% to 34%,8,9 total salpingectomy likely reduces this risk by 49% to 65%.10,11

With this new evidence, McAlpine and colleagues initiated an educational campaign, targeting all ObGyns in British Columbia, which outlined the role of the fallopian tube in ovarian cancer and urged the consideration of total salpingectomy for permanent contraception in place of occlusive or partial salpingectomy procedures. They found that this one-time targeted education increased the use of total salpingectomy for permanent contraception from 0.5% at 2 years before the intervention to 33.3% by 2 years afterwards.12 On average, laparoscopic bilateral salpingectomy took 10 minutes longer to complete than occlusive procedures. Most importantly, they found no significant differences in complication rates, including hospital readmissions or blood transfusions.

Although our community can be applauded for the rapid uptake of concomitant bilateral salpingectomy at the time of benign hysterectomy,12,13 offering total salpingectomy for permanent contraception is far from common practice. Similarly, while multiple studies have been published to support the practice of opportunistic salpingectomy at the time of hysterectomy, little has been published about the use of bilateral salpingectomy for permanent contraception until this past year.

In this article, we review some of the first publications to focus specifically on the feasibility and safety profile of performing either immediate postpartum total salpingectomy or interval total salpingectomy in women desiring permanent contraception.

Family Planning experts are now strongly discouraging the use of terms like “sterilization,” “permanent sterilization,” and “tubal ligation” due to sterilization abuses that affected vulnerable and marginalized populations in the United States during the early-to mid-20th century.

In 1907, Indiana was the first state to enact a eugenics-based permanent sterilization law, which initiated an aggressive eugenics movement across the United States. This movement lasted for approximately 70 years and resulted in the sterilization of more than 60,000 women, men, and children against their will or without their knowledge. One of the major contributors to this movement was the state of California, which sterilized more than 20,000 women, men, and children.

They defined sterilization as a prophylactic measure that could simultaneously defend public health, preserve precious fiscal resources, and mitigate menace of the “unfit and feebleminded.” The US eugenics movement even inspired Hitler and the Nazi eugenics movement in Germany.

Because of these reproductive rights atrocities, a large counter movement to protect the rights of women, men, and children resulted in the creation of the Medicaid permanent sterilization consents that we still use today. Although some experts question whether the current Medicaid protective policy should be reevaluated, many are focused on the use of less offensive language when discussing the topic.

Current recommendations are to use the phrase “permanent contraception” or simply refer to the procedure name (salpingectomy, vasectomy, tubal occlusion, etc.) to move away from the connection to the eugenics movement.