CASE: Is vacuum extraction right for this delivery?

A 41-year-old woman (G2P2002) is at term in her third pregnancy, and the fetus exhibits prolonged deceleration that does not resolve while the mother pushes from a +3 station. The fetus, estimated to weigh 8 lb, is in the occiput anterior (OA) position. The mother is willing to consider vaginal extraction, and you must weigh the factors that may influence successful delivery.

Vacuum extraction (VE) is an effective method to facilitate delivery. From 2007 to 2013, VE was used to facilitate about 3% of vaginal deliveries in the United States.1 By contrast, cesarean delivery rates over the same period averaged about 30%.2

Controversy exists on the pros and cons of operative vaginal deliveries versus cesarean delivery, as well as on the instruments and operational approaches used. While opinion tends to be resolute and influential, evidence remains inconclusive.

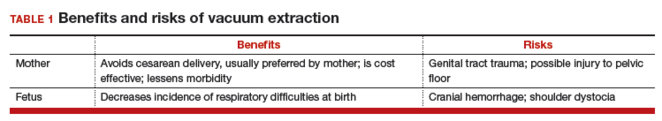

Multiple factors influence a decision on whether to choose VE. The clinician’s own bias regarding delivery routes and comfort level with performing VE are important. The patient, too, may have preconceived opinions about VE. Knowing the indications for VE and its benefits and risks (TABLE 1) can help the patient make an informed choice and the counseling on which will be needed in obtaining the patient’s informed consent. The expectations and desires of the patient in concert with the experience and skill of the clinician will serve to achieve the optimal decision.

Indications for VE

Maternal indications for the use of VE include prolongation or arrest of the second stage of labor. Another indication is the need to shorten the second stage due to a maternal cardiac or cardiovascular disorder or due to maternal exhaustion.

Fetal indications include nonreassuring fetal status or a need to correct for minor degrees of malposition (asynclitism, deflexion) that historically have been addressed with the use of obstetric forceps. VE delivery in these circumstances requires a very experienced and skilled operator.

Further selection criteria

Birthweight influences the consideration of VE. Low birthweight or prematurity are contraindications to the use of VE due to concerns about fetal/neonatal bleeding. Large fetuses will have issues with cephalopelvic disproportion, thus increasing the risk for 2 disorders: shoulder dystocia and fetal cranial bleeding.

Cranial bleeding, both intracranial and extracranial, can result in serious neonatal morbidity and mortality. Bleeding may occur spontaneously or with the use of VE. In using VE, force is transmitted to the fetal scalp. The scalp then has the tendency to pull on its contents and attachments—skull bones, brain, fluids, etc. The scalp attachments include vessels at right angles to the scalp, which may be traumatized or torn by the pulling force. This may lead to subgaleal hemorrhage, a collection of blood in the large potential space below the scalp and above the aponeurosis. Enough force may be generated to deform the intracranial contents and cause intracranial bleeding.

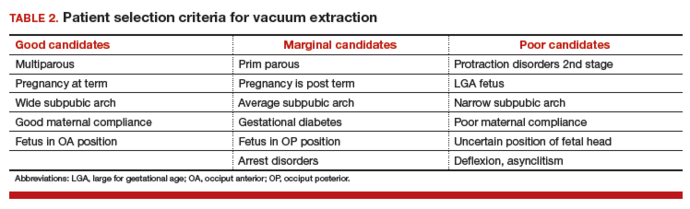

The likelihood of success with VE varies depending on maternal anatomy, the position of the fetal head, gestational age, and the presence or absence of gestational diabetes (TABLE 2).

Delivery by VE: Main considerations

After determining that a candidate is suitable for VE and obtaining informed consent, consider key operative factors:

- choice of extraction cup

- adequate anesthesia

- careful maternal positioning

- maternal bladder emptying

- review of fetal status.

Two major cup types are available: rigid and flexible.

Rigid plastic cup. This design is similar to the metal cup used by Malmström and attaches to the scalp via chignon formation. A variation of the rigid cup is the mityvac “M” that mimics the Malmström design but incorporates a semiflexible handle to facilitate proper cup placement and aid in the direction of pulling force.

Flexible cup. This type of cup flattens against the scalp with vacuum and may result in less minor scalp trauma than the rigid cup.

Greater force can be employed with rigid cup designs than with flexible cups, which can increase the chances of a successful delivery when the fetus is in the occiput posterior (OP) position. Flexible designs tend to cause less damage to the scalp than the rigid cup but are reported to have a higher failure rate.

Cardinal rule of any procedure. Prior to cup placement, remember this rule: abandon the procedure if it proves too difficult. Most deliveries will occur with 3 or 4 pulls.3 Difficulties include:

- failure to gain station with the initial pull

- repetitive cup pop-offs (3 or more)

- an excessive duration of the procedure (>10 minutes).

Less than optimal placement of the vacuum extractor will increase the risk of scalp trauma, particularly in nulliparous women.3