Over the past decade, androgen replacement prescriptions for men ≥40 years of age have increased 3-fold, according to one study.1 While one could argue this trend represents greater attention to an underdiagnosed problem, the study of prescription claims for almost 11 million men found that a quarter of them did not have a testosterone level documented in the 12 months prior to receiving treatment.1

At the same time, sales of testosterone products totaled about $2.4 billion dollars in 2013, a number projected to top $4 billion by 2017.2 The increase in prescribing is thought to be due, at least in part, to direct-to-consumer marketing techniques encouraging patients to seek medical attention if they are experiencing non-specific symptoms, such as fatigue and lack of energy, because their “problem” could be due to low testosterone.

Testosterone begins to decrease after age 40

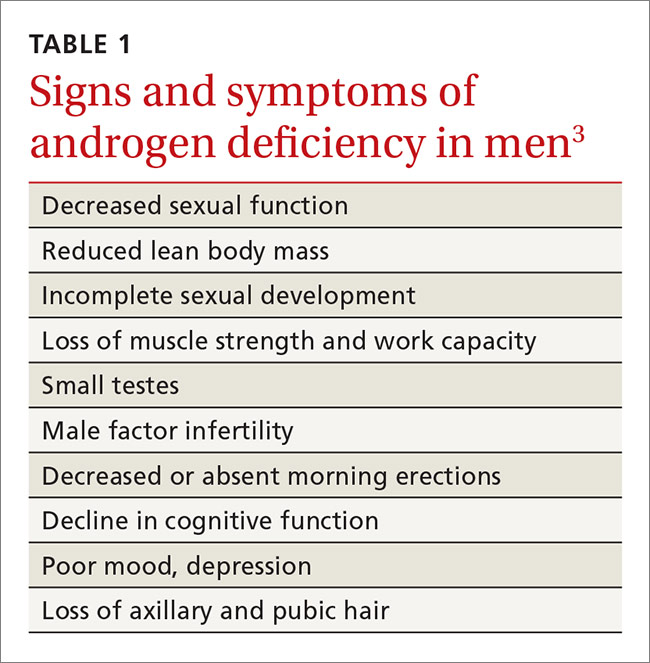

The Endocrine Society defines “androgen deficiency” as low serum testosterone (generally <280 ng/dL for healthy young men) along with signs and symptoms of hypogonadism, including decreased sexual function; loss of axillary and/or pubic hair; low bone mineral density; loss of motivation and/or concentration; poor mood or depression; decline in cognitive function; and loss of muscle strength and work capacity (TABLE 1).3

Primary vs secondary hypogonadism. Primary (or hypogonadotropic) hypogonadism results when the testes fail to produce adequate testosterone in the presence of normal serum luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) levels. Secondary hypogonadism is pituitary or hypothalamic in origin. Patients with primary hypogonadism will have high LH and FSH levels, whereas patients with secondary hypogonadism will have low or normal LH and FSH levels.4 The Endocrine Society recommends checking LH and FSH levels in all patients with hypogonadism to differentiate the primary from the secondary type.3 Patients with late onset primary hypogonadism do not require any further evaluation. In young men, it is important to consider Klinefelter syndrome. This diagnosis can be determined with a karyotype. In patients with secondary hypogonadism, checking serum iron, prolactin, and other pituitary hormones, and getting a magnetic resonance imaging scan of the sella turcica may be indicated. This will rule out infiltrative diseases, such as hemochromatosis, prolactinoma, and hypothalamic or pituitary neoplasm.

Testosterone is present in the body in 3 forms: free testosterone, albumin-bound testosterone, and testosterone bound to sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG). In young healthy men, only 1% to 2% of testosterone is free, about 40% is albumin-bound and readily dissociates to free testosterone, and the remainder is tightly bound to SHBG, which does not readily dissociate and is therefore biologically unavailable.5 The amount of SHBG increases with age, decreasing the amount of bioavailable testosterone.

Serum levels of testosterone remain approximately stable until about age 40. After age 40, total levels of testosterone decrease by 1% to 2% annually, and serum free testosterone levels decrease by 2% to 3% annually.6 Testing of free testosterone levels is recommended when a patient falls in the low normal range of total testosterone (see below).

Testosterone screening: How and for whom?

The Endocrine Society, consistent with the American Urological Association and the European Association of Urology, recommends against screening the general population for testosterone deficiency, fearing overdiagnosis and treatment of asymptomatic men.3,7,8

The Endocrine Society’s recommendation for targeted screening states that for men with chronic diseases (eg, diabetes mellitus, end-stage renal disease, and chronic obstructive lung disease), measurement of testosterone may be indicated by symptoms such as sexual dysfunction, unexplained weight loss, weakness, or mobility limitation. The recommendation also states that in men with other conditions (eg, pituitary mass, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-associated weight loss, low-trauma fracture, or treatment with medications that affect testosterone production), measurement of testosterone may be indicated, regardless of symptoms.3 The United States Preventive Services Task Force does not have any specific recommendations regarding screening for hypogonadism in men.

Start with total serum testosterone

Measuring total serum testosterone should be the initial test for suspected testosterone deficiency. Testosterone levels vary throughout the day, peaking in the morning. As a result, levels should generally be measured before 10 am.

Lab values to watch for. Again, the lower limit of the normal testosterone range in healthy young men is 280 to 300 ng/dL, but may vary depending on the laboratory or assay used.3 If the level is abnormal (<280 ng/dL), repeat the test at least a month later prior to initiating testosterone replacement.3 For men with values in the low normal range and clinical symptoms, obtain levels of free testosterone to confirm the diagnosis.

Patients with chronic diseases, such as obesity, diabetes mellitus, liver disease, nephrotic syndrome, or thyroid disease, are more likely to have an increase in SHBG. For these patients, check free testosterone levels in the setting of symptoms and a low-to-normal total testosterone level.9 If a patient has symptoms of hypogonadism and a total testosterone level in the low normal range, as well as a free testosterone level that is less than the lower limit of normal for a laboratory (typically around 50 ng/dL), it is reasonable to offer testosterone replacement.

Medications such as glucocorticoids and opioids can affect testosterone levels, as can acute or subacute illness.10 Therefore, do not measure testosterone levels while a patient is receiving these medications, and wait until a patient has recovered from being ill before doing any testing.

Temper your response with older men. Many men >65 years old may have testosterone levels below the normal range for healthy, young counterparts. This decline is of uncertain clinical significance; it remains unclear if lower levels in older men result in health problems. Some have suggested establishing age-adjusted normal values, and recommend not initiating testosterone replacement therapy in older men until serum levels are below 200 ng/dL, rather than 280 ng/dL, which is the generally accepted lower limit for younger populations.3,11,12