Diagnosis and Workup

Laboratory Evaluation

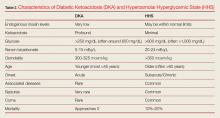

In addition to hyperglycemia, another key finding in DKA is elevated anion gap metabolic acidosis resulting from ketoacid production. Laboratory evaluation will demonstrate a pH less than 7.3 and serum bicarbonate level less than 18 mEq/L; urinalysis will be positive for ketones.

Though HHS patients also present with hyperglycemia, laboratory evaluation will demonstrate no, or only mild, acidosis, normal pH (typically >7.3), bicarbonate level greater than 18 mEq/L, and a high-serum osmolality (>350 mOsm/kg). While urinalysis may show low or no ketones, patients with HHS do not develop the marked ketoacidosis seen in DKA. Moreover, glucose values are more elevated in patients with HHS, frequently exceeding 1,000 mg/dL.

Signs and Symptoms

Patients with either of these hyperglycemic crises often present with fatigue, polyuria, and polydipsia. They appear dehydrated on examination with dry mucous membranes, tachycardia, and in severe cases, hypotension. Patients with HHS often present with altered mental status, seizures, and even coma, while patients with DKA typically only experience changes in mental status in the most severe cases (Table 2). As many as one-third of patients with a hyperglycemic crisis will have an overlapping DKA/HHS syndrome.1-3 With respect to patient age, HHS tends to develop in older patients who have type 2 diabetes and several underlying comorbidities.2

Precipitating Causes of DKA and HHS

The five causes of DKA/HHS can be remembered as the “Five I’s”: (1) infection; (2) infarction; (3) infant (pregnancy), (4) indiscretion, and (5) [lack of] insulin (Table 3).

Infection. Infection is one of the most common precipitating factors in both DKA and HHS.1 During the history intake, the EP should ask the patient if he or she has had any recent urinary and respiratory symptoms, as positive responses prompt further investigation with urinalysis and chest radiography. A thorough dermatological examination should be performed to assess for visible signs of infection, particularly in the extremities and intertriginous areas.

When assessing patients with DKA or HHS for signs of infection, body temperature to assess for the presence of fever is not always a reliable indicator. This is because many patients with DKA/HHS develop tachypnea, which can affect the efficacy of an oral thermometer. In such cases, the rectal temperature is more sensitive for detecting fever. It should be noted, however, that some patients with severe infection or immunocompromised state—regardless of the presence or absence of tachypnea—may be normothermic or even hypothermic due to peripheral vasodilation—a poor prognostic sign.3 Blood and urine cultures should be obtained for all patients in whom infection is suspected.

Laboratory evaluation of patients with DKA may demonstrate a mild leukocytosis, a very common finding in DKA even in the absence of infection; leukocytosis is believed to result from elevated stress hormones such as cortisol and epinephrine.3

Infarction. Infarction is another important underlying cause of DKA/HHS and one that must not be overlooked. Screening for acute coronary syndrome through patient history, electrocardiography, and cardiac biomarkers should be performed in all patients older than age 40 years and in patients in whom there is any suggestion of myocardial ischemia.

A thorough neurological examination should be performed to assess for deficits indicative of stroke. Although neurological deficits can be due to severe hyperglycemia, most patients with focal neurological deficits from hyperglycemia also have altered mental status. Focal neurological deficits without a change in mental status are more likely to represent an actual stroke.4

Infant (Pregnancy). Pregnant patients are at an increased risk of developing DKA for several reasons, most notably due to the increased production of insulin-antagonistic hormones, which can lead to higher insulin resistance and thus increased insulin requirements during pregnancy.5 A pregnancy test is therefore indicated for all female patients of child-bearing age.

Indiscretion. Non-compliance with diet, such as taking in too many calories without appropriate insulin correction, and the ingestion of significant amounts of alcohol can lead to DKA. Eating disorders, particularly in young patients, may also contribute to recurrent cases.3

[Lack of] Insulin. In insulin-dependent diabetes, skipped insulin doses or insulin pump failure can trigger DKA/HHS. In fact, missed insulin doses are becoming a more frequent cause of DKA than infections.1

Both DKA and HHS are usually triggered by an underlying illness or event. Therefore, clinicians should always focus on identifying precipitating causes such as acute infection, stroke, or myocardial infarction, as some require immediate treatment. In fact, DKA or HHS is rarely the primary cause of death; patients are much more likely to die from the precipitating event that caused DKA or HHS.1,3