Data Analysis

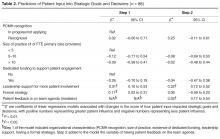

Data was analyzed in Stata version 13.0 (College Station, TX). Means and frequencies were used to characterize the sample. Stepwise multivariate modeling was used to identify factors associated with patient engagement outcomes. Organizational characteristics (size of the practice, PCMH recognition status, dedicated funding, leadership support, and having a formal strategy) were included as potential independent variables in Step 1 of the model for each of the 2 hypothesized patient engagement outcomes. Because we theorized that it might be a factor associated with the outcomes that was in turn influenced by clinic characteristics, the process of allocating dedicated time in team meetings to discuss and consider actions to take in response to patient feedback was included as a predictor in Step 2 of each model. Survey items that were not answered were treated as missing data (not imputed). We tested for multiple collinearity using variance influence factors.

Results

Of the 470 CHCs who were invited to participate in the survey, 97 took part, for a response rate of 21%. On individual items the percentage of missing data ranged from 0 to 8%. The majority of respondents (67%; 64/95) reported having 10 or more FTE primary care providers ( Table 1 ). Half of respondents reported that their CHC had received PCMH recognition (52%; 50/97), mostlythrough the NCQA, and one-third reported that they had dedicated funding for patient engagement activities (30%; 28/95). Respondents primarily belonged to clinical (43%) or operational (40%) areas of leadership in their practices.The most common mechanisms for receiving patient feedback were surveys (94% of respondents; 91/97) and suggestion boxes (57%; 55/97; Table 1). A third of respondents reported soliciting patient feedback on information materials (33%; 32/97), and almost a third involved patients in selecting referral resources (28%; 27/97). As for ongoing participation, 69% (67/97) of respondents reported involving patients on advisory boards or councils, and 36% (35/97) invited patients to take part in quality improvement committees. Other common activities included inviting patients to conferences or workshops (30%; 29/97) and asking patients to lead self-management or support groups (29%; 28/97).

Most respondents (82%; 77/93) agreed or strongly agreed that patient engagement was worth the time it required. About a third (35%; 32/92) reported having a formal strategy for recruiting and engaging patients in an advisory capacity. About half (52%; 49/94) reported setting aside time in team meetings to discuss patient feedback, although fewer (39%; 35/89) reported that their front line staff met regularly with patients to discuss clinic services and programs. Two-thirds of respondents (68%; 64/94) reported that their leadership would like to find more active ways to involve patients in practice improvement. Less than half (44%; 39/89) felt that they were successful at engaging patient advisors who represented the diversity of the population served. When considering downsides of patient engagement, few agreed that revealing the workings of the clinics to patients would expose the clinic to too much risk (8%; 7/89) or that patients would make unrealistic requests if asked their opinions (14%; 12/89).

In Step 1 of the multivariate models, clinic leadership support and having a formal strategy for recruiting and engaging patients was associated with greater patient engagement in shaping strategic goals and priorities ( Table 2