The annual incidence of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury in the general US population is estimated at 1 in 3000, or approximately 100,000 ACL injuries per year.1 The incidence of meniscal injuries after ACL tears ranges from 34% to 92%,2 with peripheral posterior horn tears of the medial meniscus accounting for 40% of the meniscal pathology.3

Although several meniscal tear patterns and their treatments have been described in the literature, posterior medial meniscal capsular junction (MCJ) tears have not been adequately addressed. Thijn4 found the accuracy of routine anterior portal arthroscopy in identifying medial meniscus tears was only 81%. Gillies and Seligson5 found a 25% arthroscopic false-negative rate caused by failure to detect peripheral tears in the posterior horn of the medial meniscus.

We reviewed 781 (517 male, 264 female) patients who underwent ACL reconstruction at our clinic and found a 12.3% incidence of MCJ tear with primary ACL injury and a 23.6% incidence of MCJ tear with revision ACL reconstruction. We believe this is a specific injury pattern. If not looked for during arthroscopy, it can be missed. Whether this tear pattern behaves differently from a posterior medial meniscus tear is yet to be determined.

To address such tear patterns, with or without ACL reconstruction, we use an arthroscopic repair technique that shows direct visualization of the tear and its reduction.

Materials and Methods

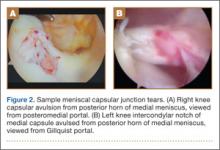

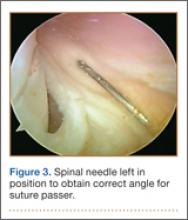

The standard anterior medial and lateral arthroscopic portals are established. A 30° scope is placed in the anterior lateral portal, and an arthroscopic shaver is used to débride the ACL remnants, including the footprint and the femoral insertion site. The camera is then adjusted to look straight down. Next, it is placed between the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) and the medial femoral condyle and advanced toward the posterior capsule. It is then adjusted to view medially (Figure 1). If there is a tear (Figures 2A, 2B), a posterior medial portal (described by Gillquist and colleagues6) is established using an 18-gauge spinal needle for localization followed by a small stab incision through the skin. The spinal needle is left in position to obtain the correct angle for the suture passer (Figure 3). A 70° Hewson suture passer (Smith & Nephew, Memphis, Tennessee) is passed through the posterior medial portal.

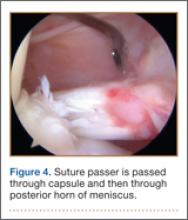

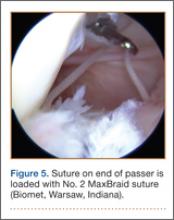

Once inside the joint, the suture passer is passed through the capsule and then through the posterior horn of the meniscus (Figure 4). A loop grasper is used to grab the suture on the end of the passer and then is brought out the posterior medial portal and loaded with a No. 2 MaxBraid suture (Biomet, Warsaw, Indiana) (Figure 5). In some cases, the suture passer’s wire goes out the notch toward the anterior aspect of the knee. If this occurs, the loop grasper can be used to grab this wire from the anterior medial portal and load with the MaxBraid suture.

Standard arthroscopic knot-tying techniques are used under direct visualization showing the reduction of the capsule to the meniscus (Figure 6). This is done from the posterior medial portal. The excess suture is cut with an arthroscopic suture cutter in the standard fashion. In the rare case of an intact ACL with this same tear pattern, the same technique can be used. If there is difficulty moving past the intact ACL and PCL, a posterior lateral portal can be used as another accessory portal. The arthroscope can then be placed in the posterior lateral portal, while the posterior medial portal can be used as the working portal. Care must be taken in either technique to avoid soft-tissue bridges.

Discussion

Previous biomechanical studies have shown the meniscus to be important to knee stability. In an ACL-deficient knee, the posterior medial meniscus is important as a secondary stabilizer, and for that reason it is crucial to identify and repair tears there to avoid risking extra force on the ACL graft.7,8 We think an MCJ tear can potentially compromise knee stability as well, so there is a need to examine the posterior aspect of the knee during every knee arthroscopy. However, biomechanical studies must be performed to validate this theory.

To assess whether orthopedists in general are aware of and concerned about MCJ tears, a survey was e-mailed to members of the Arthroscopy Association of North America (AANA) and the American Sports Medicine Fellowship Society (ASMFS). Sixty-seven orthopedic surgeons who perform ACL reconstruction surgeries responded to some or all of the following questions. Nearly half (48%) of the surgeons said they always assess the posteromedial MCJ by placing the camera between the PCL and the medial femoral condyle. Only 25% said MCJ tears should be repaired always, but another 64% said these tears should be repaired sometimes. Thus, 89% responded that at least some MCJ tears should be repaired. Most (88%) said these tears could sometimes or always be a source of chronic pain. Also, 92% said these tears could sometimes or always change the contact pressures in the knee, and 66% said these tears could sometimes or always change the rotational stability of the knee. Finally, 60% said MCJ tears could sometimes or always affect ACL graft failure. These data show a need to determine an appropriate surgical technique that will help treat MCJ tears.