Take-Home Points

- Loss of tissue homeostasis from overuse or injury produces pain.

- In patients with AKP, treatment should begin with activity modification with the envelope of function; pain-free rehabilitation; an anti-inflammatory program of cold, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and sometimes steroid injection.

- Physical therapy should be done without painful exercise, otherwise it could be counter-productive.

- Patellofemoral syndrome and chondromalacia are not valid clinical diagnoses. A more specific diagnosis based on careful clinical evaluation to determine anatomic origin of pain will better direct treatment.

- Even when lateral retinacular tightness is identified as the probable source of pain, surgery is seldom required.

Symptoms of patellofemoral pain (PFP) without a readily identifiable cause are perhaps the most common yet vexing clinical complaint heard by orthopedic surgeons worldwide. PFP typically occurs over the anterior knee, is often diffuse, and worsens with prolonged knee flexion and the use of stairs. Some prefer the term anterior knee pain (AKP) because we do not always know the pain is patellofemoral in anatomical origin; we know only that it is felt in the anterior knee. Pain is inherently and irreducibly a subjective phenomenon, a function of very discrete central nervous system activity within the sensory area of the contralateral cerebral cortex to the symptomatic knee. Pain is purely subjective and therefore by definition not objectively and consistently measurable between patients. Emotions play a role in pain as well, and somatization resulting in knee pain is a well-known phenomenon, particularly in adolescent women related to stress or even abuse. There is no imaging study that can be used to guide the rational treatment of pain. The best we can do is to ask patients to draw pain diagrams, which provide useful information proven to correlate with areas of tenderness.1

Although many have referred to patients with PFP as having patellofemoral pain syndrome, we reject that term, as it implies a clearly defined syndrome—a consistent set of symptoms, signs, and test results—that does not exist. More complex AKP cases, such as those involving major trauma, complex regional pain syndrome, or multiple operative procedures, are beyond the scope of this article, though many of the principles discussed are applicable. Surprisingly, despite decades of research and clinical experience with a vast number of patients, there still is controversy regarding the underlying etiology of the symptoms and the best, safest treatment.

Primum non nocere. First, do no harm. Let us understand how to reach that noble goal.

Our Hypothesis: Loss of Homeostasis Causes Pain

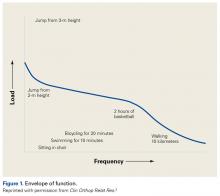

Homeostasis is a natural process of maintaining relatively stable and asymptomatic physiologic conditions in all organ systems under fluctuating environmental conditions. We hypothesize that pain is the result when load applied to musculoskeletal tissues exceeds the ability to maintain homeostasis. As in other organ systems, in musculoskeletal tissues homeostasis is restored and maintained with appropriate treatment. To illustrate this hypothesis, Dr. Dye coined the term envelope of function (EOF). A combination of magnitude and frequency of load causes loss of homeostasis; with respect to the knee, activity or injury pushes it out of its acceptable EOF in which homeostasis is maintained (Figure 1).2

When the total amount of load pushes into the zone of supraphysiologic overload, homeostasis is lost and pain occurs. With rest, time, and appropriate treatment, homeostasis can be restored. A simple example is muscle soreness that occurs after overuse and resolves over a few days. When the knee, or any joint, operates outside its EOF longer or with increased magnitude of load, structural failure may occur. If lack of homeostasis causes pain, the solution to pain is to restore homeostasis.The therapeutic recommendations that follow from this new biocentric paradigm of joint function are quite different from those associated with hypotheses attributing AKP to chondromalacia and malalignment. This new “common sense” approach, which never encourages treatment that makes symptoms worse, recognizes healing as a complex, rate-limited biological phenomenon that can take time to achieve, especially within a harsh and unforgiving biomechanical environment such as the human patellofemoral joint.

Traditional Explanations and Treatment Strategies

In traditional teaching, 2 causes of AKP have been prominent: chondromalacia patella (CMP) (softening of the articular surface of the patella) and malalignment of the extensor mechanism. Ironically, many of the worst AKP cases are iatrogenic, resulting from surgery to “correct” CMP and/or patellofemoral malalignment or maltracking. Even exercises encouraged by ill-informed physical therapists—such as excessive squats and lunges—can easily worsen AKP symptoms. We think the clinical failure of these traditional methods reflects a profound misunderstanding of the most common cause of AKP.