The musculotendinous components of the elbow are essential to providing dynamic functional resistance to valgus stress.11 These components are flexor-pronator musculature that originate from the medial epicondyle. Listed proximally to distally, the flexor-pronator muscles include pronator teres, flexor carpi radialis (FCR), palmaris longus, flexor digitorum superficialis, and the flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU).

Pathomechanics

Once familiarized with the relevant function anatomy, it is crucial to understand the mechanics of throwing in order to understand the pathomechanics of VEO. The action of overhead throwing has been divided into 6 phases.6,12-16 Phase 4, acceleration, is the most relevant when discussing forces on elbow, since the majority of forces are generated during this state. Phase 4 represents a rapid acceleration of the upper extremity with a large forward-directed force on the arm generated by the shoulder muscles. Additionally, there is internal rotation and adduction of the humerus with rapid elbow extension terminating with ball release. The elbow accelerates up to 600,000°/sec2 in a miniscule time frame of 40 to 50 milliseconds.1,5 Immense valgus forces are exerted on the medial aspect of the elbow. The anterior bundle of the UCL bears the majority of the force, with the flexor pronator mass enabling the transmission.11 The majority of injuries occur during stage 4 as a result of the stress load on the medial elbow structures like the UCL. The proceeding phases 5 (deceleration), and 6 (follow-through) involve eventual dissipation of excess kinetic energy as the elbow completely extends. The deceleration during phase 5 is rapid and powerful, occurring at about 500,000°/sec2 in the short span of 50 milliseconds.1,6,12-16 High-velocity throwing, such as baseball pitching, generates forces in the elbow that are opposed by the articular, ligamentous, and muscular portions of the arm. The ulnohumeral articulation stabilizes motion of the arm from 0° to 20° of flexion and beyond 120° of flexion. Static and dynamic soft tissues maintain stability during the remaining of 100° arc of motion.

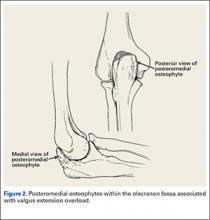

During deceleration, the elbow undergoes terminal extension resulting in the posteromedial olecranon contacting the trochlea and the olecranon fossa with subsequent dissipation of the combined valgus force and angular moment (Figure 1). This dissipation of force creates pathologic shear and compressive forces in the posterior elbow. Poor muscular control and the traumatic abutment that occurs in the posterior compartment may further add to the pathologic forces. Reactive bone formation is induced by the repetitive compression and shear, resulting in osteophytes on the posteromedial tip of the olecranon (Figure 2). Consequent “kissing lesions” of chondromalacia may occur in the olecranon fossa and posteromedial trochlea. The subsequent development of loose bodies may also occur. The presence of osteophytes and/or loose bodies may result in posteromedial impingement (PMI).

The association between PMI of the olecranon and valgus instability has been elucidated in both clinical and biomechanical investigations.17,18,19,20 Conway18 identified tip exostosis in 24% of lateral radiographs of 135 asymptomatic professional pitchers. Approximately one-fifth (21%) of these pitchers had >1.0 mm increased relative valgus laxity on stress radiographs. Roughly one-third (34%) of players with exostosis had >1.0 mm of increased relative valgus laxity, compared to 16% of players without exostosis formation. These results provide evidence for a probable association between PMI and valgus laxity. In biomechanical research, Ahmad and colleagues17 studied the effect of partial and full thickness UCL injuries on contact forces of the posterior elbow. Posteromedial compartments of cadaver specimens were subjected to physiologic valgus stresses while placed on pressure-senstive film. Contact area and pressure between posteromedial trochlea and olecranon were altered in the setting of UCL insufficiency, helping explain how posteromedial osteophyte formation occurs.

Additional biomechanical studies have also investigated the posteromedial olecranon’s role in functioning as a stabilizing buttress to medial tensile forces. Treating PMI with aggressive bone removal may increase valgus instability as well as strain on the UCL, leading to UCL injury following olecranon resection.19,20 Kamineni and colleagues19 investigated strain on anterior bundle of UCL as a function of increasing applied torque and posteromedial resections of the olecranon. This investigation was done utilizing an electromagnetic tracking placed in cadaver elbows. A nonuniform change in strain was found at 3 mm of resection during flexion and valgus testing. This nonuniform change implied that removal of posteromedial olecranon beyond 3 mm made the UCL more vulnerable to injury. Follow-up investigations looked at kinematic effects of increasing valgus and varus torques and sequential posteromedial olecranon resections.20 Valgus angulation of the elbow increased with all resection levels but no critical amount of olecranon resection was identified. The consensus in the literature indicates that posteromedial articulation of the elbow is a significant stabilizer to valgus stress.17-22 Thus, normal bone should be preserved and only osteophytes should be removed during treatment.