Function of the Glenohumeral Ligaments

The glenohumeral joint capsule has thickenings that help to stabilize the joint. The function of these glenohumeral ligaments has been evaluated biomechanically for their role in preventing translation and instability by a number of authors. The inferior glenohumeral ligament has classically been described as resisting anterior translation of the abducted arm.16 The coracohumeral ligament has been described as important to prevent inferior translation of the adducted arm.17

Interestingly, these ligaments are also the most important ligaments in resisting external rotation of the adducted arm.18 The dominant arm of throwing athletes has been shown to have increased inferior translation19 and increase external rotation.19-22 While the external rotation is partly related to bony adaptation,23,24 the ligamentous restraints to external rotation are likely under tremendous load, which may explain why Dr. Frank Jobe revolutionized the surgical treatment of the throwing athlete by performing an “instability” operation,25,26 as he believed these athletes had “subtle instability” that produced pain, but not symptoms of looseness.27

While these ligaments may exist in part to prevent translation and instability, current thinking suggests that “over-rotation” may lead to internal impingement and may be responsible for symptoms in the thrower’s shoulder,28 as SLAP lesions seem to occur easier with external rotation.29 Again, the importance of maximizing external rotation in throwing and the finding that this position is a critical moment with very high forces suggests that these ligaments may represent an adaptation to restrain external rotation while throwing.

Coracoacromial Ligament

The coracoacromial ligament is unique in that it connects 2 pieces of the same bone, and is only seen in hominids—not other primates.30 Its function has been debated for decades. This ligament is generally thought to limit superior translation of the humeral head,31,32 an effect that is critically important in patients with rotator cuff tears 33,34 Its importance is demonstrated by the fact that it seems to regenerate after it has been resected.35,36 Yet release or resection of this ligament has been a standard treatment for shoulder pain for decades.

Its function becomes clear if one examines the coracoacromial ligament with respect to the kinematics of throwing. As mentioned above, in the late cocking phase of throwing, tremendous shear forces exist in the shoulder. Fleisig and colleagues8 estimated a superior force of 250 ± 80 N, and an anterior shear force of 310 ± 100 N. While Fleisig and colleagues8 analyzed these shear forces with respect to the development of superior and anterior labral tears, it is important to note that these shear forces are vectors that should be combined. When one does this, it becomes apparent that in the late cocking phase of throwing there is shear force in an anterosuperior direction of approximately 400 N (Figure 1). The coracoacromial ligament is positioned to restrain this tremendous force. If throwing is an important adaptation in the evolution of humans, then the function of this ligament and its importance becomes clear.

Depressed Greater Tuberosity and the Pear-Shaped Glenoid

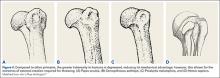

Compared to other primates, the greater tuberosity in humans sits significantly lower (Figure 4). This depression effectively decreases the moment arm of the muscle tendon unit, making the supraspinatus less powerful for raising the arm.37 In addition, by tenting the supraspinatus tendon over the humeral head, a watershed zone is created with decreased vascularity, which is thought to contribute to rotator cuff disease.38 What would be the advantage of the depressed tuberosity?

In primates, a lower tuberosity allows for more motion, particularly for arboreal travel.37 In order to throw with velocity, the humerus must achieve extremes of external rotation. A large tuberosity would limit external rotation of the abducted arm. Similarly, the pear-shaped glenoid cavity allows for the depressed tuberosity to achieve maximal external rotation. It is conceivable that a depressed greater tuberosity that allows for throwing would be an adaptation that could be favorable despite its proclivity toward rotator cuff disease in senescence.

Nature of the Subscapularis and the Role of the Long Head of the Biceps

The subscapularis is unique among rotator cuff muscles in that the upper two-thirds of the muscle is surprisingly tendinous.39 Why should this rotator cuff muscle have so much tendon material? Why is the tendon missing from the inferior one-third of the muscle? This situation is not optimal to prevent anterior glenohumeral instability, where inferior tendon material would be preferred.40

The function of the tendon of the long head of the biceps has long been debated and remains unclear.41-43 Cadaver experiments suggest the long head of the biceps provides glenohumeral joint stability in a variety of directions and positions, yet in vivo studies may not show this effect. Electromyography studies show little activity of the long head of the biceps with shoulder motion when the elbow is immobilized, leading some to suggest it is important as a passive restraint.43 This lack of understanding has led some to believe the biceps is not important and can be sacrificed without much concern.42,43