Rotator cuff injuries can be a source of debilitating pain and dysfunction in athletes at all levels, occasionally precluding return to competitive sport. Overhead athletes place extraordinary physiologic demands on the shoulder, as humeral angular velocities of 7000° to 8000° per second and rotational torques higher than 70 Nm have been measured during the baseball pitch.1 Repetitive supraphysiologic loading of the rotator cuff throughout the coordinated phases of throwing can result in a characteristic spectrum of shoulder pathology in overhead throwers. Several studies have demonstrated partial-thickness articular-sided rotator cuff tears (RCTs) in the area of the posterior supraspinatus and anterior infraspinatus tendons.2-4 Although the precise mechanism remains unclear, plausible explanations for the pathogenesis of these injuries include eccentric tensile and shear forces that lead to tendon failure with repetitive throwing, as well as internal impingement (mechanical impingement of the aforementioned tendons against the posterosuperior glenoid at 90° of shoulder abduction and maximum external rotation).5,6

Whereas partial-thickness articular-sided RCTs have been described in overhead athletes with rotator cuff pathology, full-thickness tears are encountered less often.7,8 Accordingly, there is a paucity of literature on clinical outcomes in professional baseball players with these injuries. To our knowledge, only 2 studies have investigated functional outcomes of open surgical repair of full-thickness tears in this population, and the outcomes have been uniformly poor.8,9

An anatomical description of rotator cuff anatomy has demonstrated a consistent pattern of supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendon insertion relative to the articular surface, biceps groove, and the bare area of the humerus.10 Using gross and microscopic analyses, the authors noted that the supraspinatus tendon inserted immediately adjacent to the articular margin, and the infraspinatus and teres minor tapered laterally away from the margin to form the bare area. Detailed knowledge of the insertional anatomy of the rotator cuff is important, as surgical repair should recreate the broad footprint to restore normal biomechanics and increase the surface area available for healing.11,12 Medial advancement of the rotator cuff insertion during surgical repair can have deleterious biomechanical effects on glenohumeral motion.11

Given the unfavorable results found after routine open repair of full-thickness tears, we altered our approach to these injuries and adopted an arthroscopic technique in which the tendon is repaired immediately lateral to the anatomical footprint. Research studies have demonstrated that chronic stress from repetitive throwing can lead to attenuation of soft-tissue restraints, and we think preservation of these adaptive changes after surgical repair may be important for these athletes to maintain extraordinary glenohumeral rotation and achieve high throwing velocities.13 We conducted a study to describe the lateralized repair technique for full-thickness RCTs and to report functional outcomes in Major League Baseball (MLB) pitchers treated with this procedure at minimum 2-year follow-up. We hypothesized that use of this novel technique would result in a higher rate of return to preinjury level of play in comparison with open rotator cuff repair in comparable cohorts, as reported in other studies.8,9

Materials and Methods

After obtaining Institutional Review Board approval for this study, we performed a retrospective chart review of MLB players treated by Dr. Altchek. We identified all professional baseball players who received a diagnosis of full-thickness RCT after preoperative magnetic resonance imaging with subsequent confirmation during surgery. Any patient who underwent arthroscopic repair using the lateralized footprint technique was included in the study. Demographic and preoperative injury information was collected from the chart, and final follow-up data were collected at the last available clinic visit. From available team records, we also obtained return-to-play data and objective pitching statistics: seasons played, games played, innings pitched, strikeouts per 9 innings, walks per 9 innings, and earned run average.

Surgical Technique

We routinely perform arthroscopic rotator cuff repairs with the patient under regional anesthesia in the beach-chair position. The operative extremity is placed in a Spider Limb Positioner (Smith & Nephew) to facilitate easy manipulation of the arm throughout the procedure. A standard posterior portal is established, and then an anterior portal is placed in the superolateral aspect of the rotator interval directly anterior to the leading edge of the supraspinatus tendon. A lateral portal created 2 to 3 cm distal to the anterolateral margin of the acromion may be used as an additional working portal. A thorough diagnostic arthroscopy is performed to evaluate the glenohumeral joint for any concomitant intra-articular pathology. Particular attention is directed to inspection of the superior labrum, biceps tendon, and capsuloligamentous structures, as injuries to these structures are often associated with rotator cuff pathology in overhead athletes.

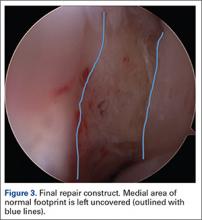

Once presence of an RCT is confirmed, a thorough subacromial bursectomy is performed to help with visualization and inspection of the injury. The tissue is provisionally grasped and mobilized to measure the amount of available tendon excursion. In this unique population, the vast majority of injuries are diagnosed in an expeditious manner, thereby precluding the presence of significant retraction, poor tissue quality, and inadequate mobilization of the tendons. The greater tuberosity is identified, and the area immediately adjacent to the articular margin is abraded with a mechanical shaver to enhance healing potential. For supraspinatus tears, an anchor is placed immediately lateral to the articular margin in the region of the anterior attachment of the rotator cable (Figure 1). The posterior anchor is placed about 10 to 15 mm lateral to the articular margin to reattach the infraspinatus tendon (Figure 2). When the medial row sutures are tied down, anatomical placement of these anchors effectively re-creates the bare area described by Curtis and colleagues10 (Figure 3). In most cases, the medial row sutures are left intact and fixed laterally with a knotless anchor to provide a transosseous equivalent (double-row) repair.