Adolescents were instructed to complete the PHR independently without the help of their caregivers. After completing the form, the social worker reviewed the answers and/or asked participants’ perspectives about communicating health information to providers. A copy of the completed PHR was provided to the adolescent to promote continued education regarding medical history knowledge. The retrospective review of the PHR answers and participants’ characteristics was approved by the institutional review board with a waiver of consent from participants.

Statistical Methods

PHR answers were compared with each individual’s electronic medical record (EMR) for accuracy of responses. PHR responses were considered accurate only if they matched the information in the EMR. PHR items absent in the EMR were not coded (inability to verify the accuracy of responses) to capture the most accurate depiction of adolescents’ medical history knowledge. Coding was checked by at least 2 coders for response accuracy. Due to lack of EMR information for certain items, we could not verify the accuracy of many PHR items. Therefore, only items with at least 75% of data verified (across all patients who completed the PHR) were included in subsequent analyses.

Using SPSS (version 18), an agreement percentage was calculated for each patient across verifiable items and used as the primary outcome measure of knowledge accuracy. We used t tests to investigate gender or genotype differences in medical history accuracy. To examine genotype differences, we stratified the sample by SCD genotype: HbSS/Sβ 0 thalassemia and HbSC/Sβ+ thalassemia [13].

Results

Patient Characteristics

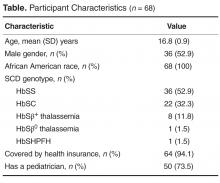

During the period of analysis, there were 95 eligible adolescents with SCD; all were approached, and 68 (71.6%) completed the PHR. Reasons for non-completion included recurrent missed visits, lack of time during the visit, or refusal. Of the 68 who completed the PHR, all were African American, 52.9% were male, and their mean age was 16.8 (± 0.9; range, 15–18) years ( Table). Completion of the PHR took on average 15 minutes.Knowledge Accuracy Among Adolescents with SCD

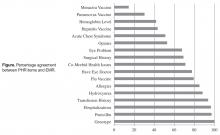

Seventeen items in 6 PHR domains had the highest number of data points (at least 75% verified), and therefore were the only items that could be analyzed. Analyzed items included information about sickle cell genotype, eye doctor care, comorbid health issues (eg, asthma), allergies, hospitalizations, surgeries, transfusions, acute chest syndrome (ACS) episodes, eye problems, baseline hemoglobin level, and vaccination history as well as adolescents’ knowledge of current medications, including hydroxyurea, penicillin, and opioid pain medications.

The accuracy of knowledge for select items is presented in the Figure. Adolescents were accurate reporters of SCD genotype (100%), hospitalizations in the previous year (96.5%), transfusion history (93.8%), and allergies (85.2%). Knowledge deficits included previous diagnosis of ACS (50.9%), baseline hemoglobin levels (41.8%), and hepatitis (43.3%), pneumovax (30.2%), and menactra (14.5%) vaccinations. Regarding current medications, adolescents were more accurate at reporting penicillin (97.1%) and hydroxyurea (88.2%) utilization, but less accurate regarding opioid pain medications (52.9%). No participants were able to report their health history with 100% accuracy.Gender was not significantly associated with overall accuracy ( P = 0.36). A significant difference was found in sickle genotype such that individuals with HbSC/Sβ+ thalassemia genotype (mean number of items, 8.23; SD = 1.70) were more accurate reporters of their medical history than those with HbSS/Sβ 0 thalassemia genotype (mean number of items, 7.14; SD = 1.75; t(65) = –2.59, P = 0.01). Specifically, those with HbSS/Sβ 0 thalassemia genotype were significantly less accurate reporters of vaccination history (meningococcus t(60) = 3.55, P = 0.001; pneumococcus t(60) = 2.46, P = 0.02; hepatitis t(64) = 2.18, P = 0.03, eye problems t(62) = 3.62; P = 0.001, and surgical history t(62) = 2.14, P = 0.04).