Case 1: Follow-up in Community-Acquired Methicillin- Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Pharyngitis

A 73-year-old woman presented to the ED complaining of injuries she sustained following a minor fall at home. The patient’s past medical history was remarkable for diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension, cerebrovascular accident, and a history of chronic pain. During the course of evaluation, the patient mentioned that she had experienced a sore throat. In addition to X-rays, the emergency physician (EP) ordered a rapid strep test (RST). All studies were normal and the patient was discharged home.

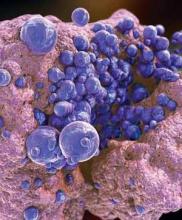

After release from the ED, the culture performed from the RST detected methicillin- resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). The positive results were reported in the electronic medical record system, but not directly to the patient’s treating EP or the patient.Over the next 2 months, the patient received medical treatment from other medical professionals, but not at the previous hospital. Reportedly, she did not complain of a sore throat during this time period. The patient did return to the same ED approximately 2 months later, complaining of cough and difficulty breathing; she died 5 days thereafter. No autopsy was performed.

A lawsuit was filed on behalf of the patient, stating the hospital breached the standard of care by not reporting the finding of MRSA directly to the treating physician, and that this led directly to the patient’s death by MRSA pneumonia. The jury returned a verdict in favor of the plaintiff for $32 million.

Discussion

This case illustrates two simple but important points: managing community-acquired MRSA (CA-MRSA) infections is a growing challenge for physicians; and hospital follow-up systems for positive findings (ie, fractures, blood cultures, etc) need to be consistently reliable.

It is estimated that 30% of healthy people carry S aureus in their anterior nares; colonization rates for the throat are much less studied. In one recent study, 265 throat swabs were collected from patients aged 14 to 65 years old, who complained of pharyngitis in an outpatient setting.1 A total of 165 S aureus isolates (62.3%) were recovered from the 265 swabs. For the S aureus isolates, 38.2% (63) grew CA-MRSA; the remaining 68.1% (102) were methicillin-sensitive S aureus (MSSA). Interestingly, of the 63 MRSA-positive swabs, over half also grew Group A Streptococcus. The natural disease progression of CA-MRSA pharyngitis is still unknown, as is what to do with a positive throat swab for CA-MRSA. While there are a few case reports of bacteremia and Lemmiere syndrome possibly related to CA-MRSA pharyngitis,2,3 more information is clearly needed. For this case, it is not possible to definitively determine the role of the positive throat swab for CAMRSA in the patient’s subsequent death.

The other teaching point in this case is much simpler and well defined. Simply put, patients expect to be informed of positive findings, whether the result is known at the time of their ED visit or sometime afterward. There needs to be a system in place that consistently and reliably provides important information to either the patient’s treating physician or to the patient. The manners in which this information is communicated are myriad and should take into account hospital resources, the role of the EP and nurse, and what works best for your locality. The “who” and “how” of the contact is not important: reliability, timeliness, and consistency need to be the key drivers of the system.

Case 2: Arterial Occlusion

A 61-year-old woman called emergency medical services (EMS) after noticing her feet felt cold to the touch and having difficulty ambulating. The paramedics noted the patient had normal vital signs and normal circulation in her legs, and she was transported to the ED without incident. Upon arrival to the ED, she was triaged as nonurgent and placed in the minor-care area. On nursing assessment, the patient’s feet were found to be cold, but with palpable pulses bilaterally. Her past medical history was significant for hypertension and DM.

The patient was seen by a physician assistant (PA), who found both feet cool to the touch, but with bilateral pulses present. She was administered intravenous morphine for pain and laboratory studies were ordered. At the time, the PA was concerned about arterial occlusion versus deep vein thrombosis (DVT) versus cellulitis. A venous ultrasound examination was ordered and shown to be negative for DVT. A complete blood count was remarkable only for mild leukocytosis. The PA discussed the case with the supervising EP; they agreed on a diagnosis of cellulitis and discharged the patient home with antibiotics and analgesics.