The severe psychiatric and somatic symptoms of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) can be debilitating and place women at increased risk for other psychiatric disorders (including major depression and generalized anxiety) and for suicidal ideation. While PMDD’s complex nature makes it an underdiagnosed condition, there are clear diagnostic criteria for clinicians to ensure their patients receive timely and appropriate treatment—thus reducing the risk for serious sequelae.

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) is categorized as a depressive disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5).1 The hallmarks of this unique disorder are chronic, severe psychiatric and somatic symptoms that occur only during the late luteal phase of the menstrual cycle and dissipate soon after the onset of menstruation.2 Symptoms are generally disruptive and often associated with significant distress and impaired quality of life.2

PMDD occurs in 3%-8% of women of childbearing age; it affects women worldwide and is not influenced by geography or culture.2 Genetic susceptibility, stress, obesity, and a history of trauma or sexual abuse have been implicated as risk factors.2-6 The impact of PMDD on health-related quality of life is greater than that of chronic back pain but comparable to that of rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis.2,7 Significantly, women with PMDD have a 50%-78% lifetime risk for psychiatric disorders, such as major depressive, dysthymic, seasonal affective, and generalized anxiety disorders, and suicidality.2

PMDD can be challenging for primary care providers to diagnose and treat, due to the lack of standardized screening methods, unfamiliarity with evidence-based practices for diagnosis, and the need to tailor treatment to each patient’s individual needs.3,8 But the increased risk for psychiatric sequelae, including suicidality, make timely diagnosis and treatment of PMDD critical.2,9

PATHOGENESIS

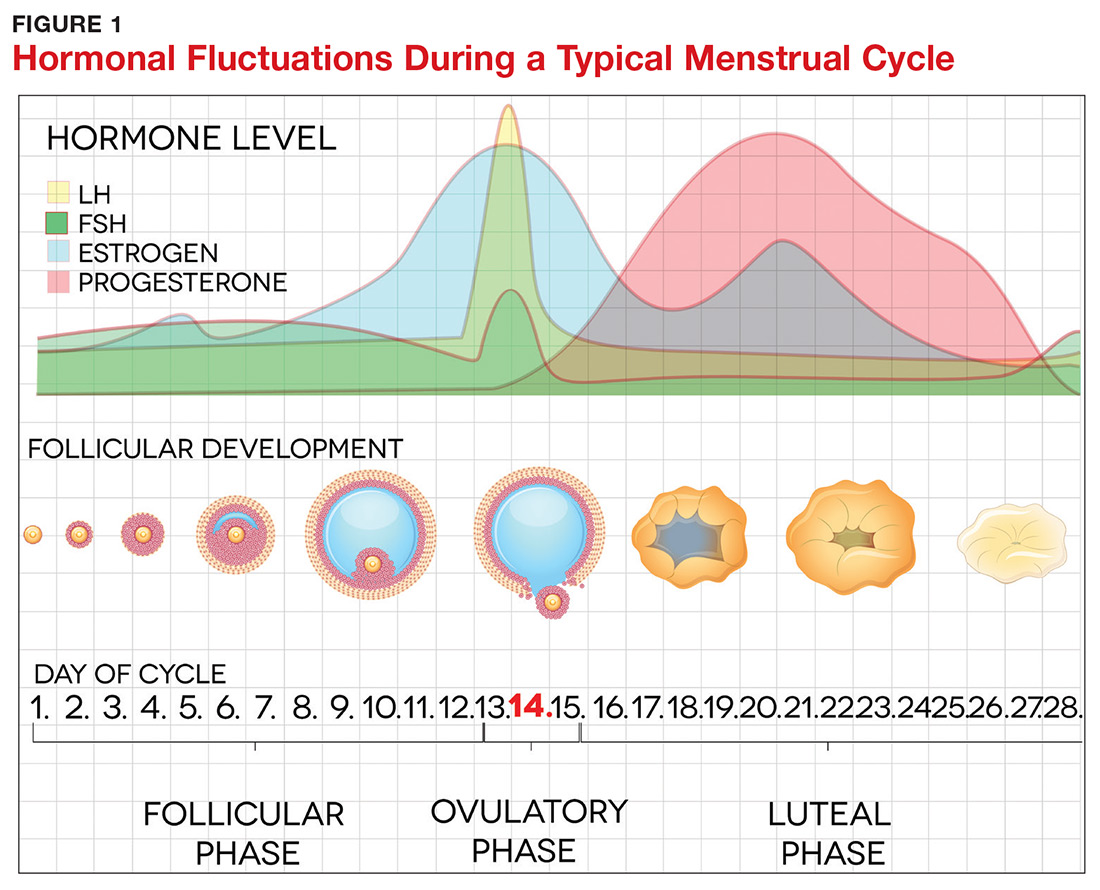

The pathogenesis of PMDD is not completely understood. The prevailing theory is that PMDD is underlined by increased sensitivity to normal fluctuations in ovarian steroid hormone levels (see the Figure) during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle.2-4,6

This sensitivity involves the progesterone metabolite allopregnanolone (ALLO), which acts as a modulator of central GABA-A receptors that have anxiolytic and sedative effects.2,3 It has been postulated that women with PMDD have impaired production of ALLO or decreased sensitivity of GABA-A receptors to ALLO during the luteal phase.2,3 In addition, women with PMDD exhibit a paradoxical anxiety and irritability response to ALLO.2,3 Recent research suggests that PMDD is precipitated by changing ALLO levels during the luteal phase and that treatment directed at reducing ALLO availability during this phase can alleviate PMDD symptoms.10

Hormonal fluctuations have been associated with impaired serotonergic system function in women with PMDD, which results in dysregulation of mood, cognition, sleep, and eating behavior.2-4,6 Hormonal fluctuations have also been implicated in the alteration of emotional and cognitive circuits.2,3,6,11,12 Brain imaging studies have revealed that women with PMDD demonstrate enhanced reactivity to amygdala, which processes emotional and cognitive stimuli, as well as impaired control of amygdala by the prefrontal cortex during the luteal phase.3,7,12

Continue to: PATIENT PRESENTATION/HISTORY