IN THIS ARTICLE

- Diagnosis

- Management

- Outcome for the case patient

An otherwise healthy 9-year-old boy is brought to the emergency department (ED) by his father for evaluation of severe pain, blurry vision, and four hours of tearing in his right eye. The patient was in school when he experienced sudden-onset irritation and scratching pain that caused him to rub his eye. He says it “feels like there is something in my eye,” but he denies any known substance or foreign body. He has no medical or surgical history, does not wear contact lenses or eyeglasses, and denies loss of vision. There is no history of recent illness or travel.

On evaluation, the patient is in no acute distress but is holding his right eye closed due to foreign-body sensation and increased photosensitivity and tearing. There is no obvious erythema or swelling in the upper or lower eyelids bilaterally. A visual acuity test with a Snellen eye chart shows 20/20 vision in the left eye and 20/50 in the right, secondary to pain, photophobia, and excessive tearing. The patient’s right sclera is significantly injected. Intraocular pressure, measured with a tonometer, is 12 to 14 mm Hg. A fluorescein stain of the eye yields no significant findings. The globe is intact.

At first glance, a slit-lamp exam shows no obvious signs of a foreign body. But much higher magnification reveals substantial conjunctival injection and numerous intracorneal linear foreign bodies in the right eye (see Figure 1 for example [not the case patient]). The anterior chamber shows no inflammatory reaction, and findings in the posterior segment are unremarkable.

The initial diagnosis is simple conjunctivitis—but closer examination reveals multiple fine, barbed hairs embedded in the patient’s right cornea. Upon further questioning, the patient reports that prior to symptom onset, he had been holding the classroom pet, a Chilean Rose tarantula, in the palm of his hands.

DISCUSSION

Foreign body injury is a common cause of ocular pain and corneal damage, which can lead to challenging complications. Ophthalmic emergencies account for 2% of ED visits in the US annually and are a major cause of visual impairment.1 But when a painful eye is the chief complaint, contact with insects, plants, or spiders is rarely included in the differential. Tarantulas are popular classroom and household pets, however, and ocular injury should be suspected in anyone who has been holding a tarantula prior to onset of pain.

Ophthalmia nodosa

Tarantulas are one of the most common arachnids known to cause ophthalmia nodosa—a granulomatous reaction of the conjunctiva or cornea to an implanted plant, insect, or spider hair that typically manifests with photophobia, irritation, and chemosis.2,3 Tarantulas, when scared or defending their eggs, shoot urticating setae at the threat—a defensive mechanism largely unknown to parents, tarantula owners, and medical professionals.

Urticating setae are found in roughly 90% of tarantula species throughout tropical and subtropical regions.4 Depending on the species, setae can be located on the distal prolateral surface of the palpal femur or the dorsum of the abdomen. They can be released when the tarantula scratches its legs against the abdominal urticating setae patch or scratches the palps against the chelicerae (appendages in front of the mouth), or when direct exterior contact is made with the abdominal setae.4

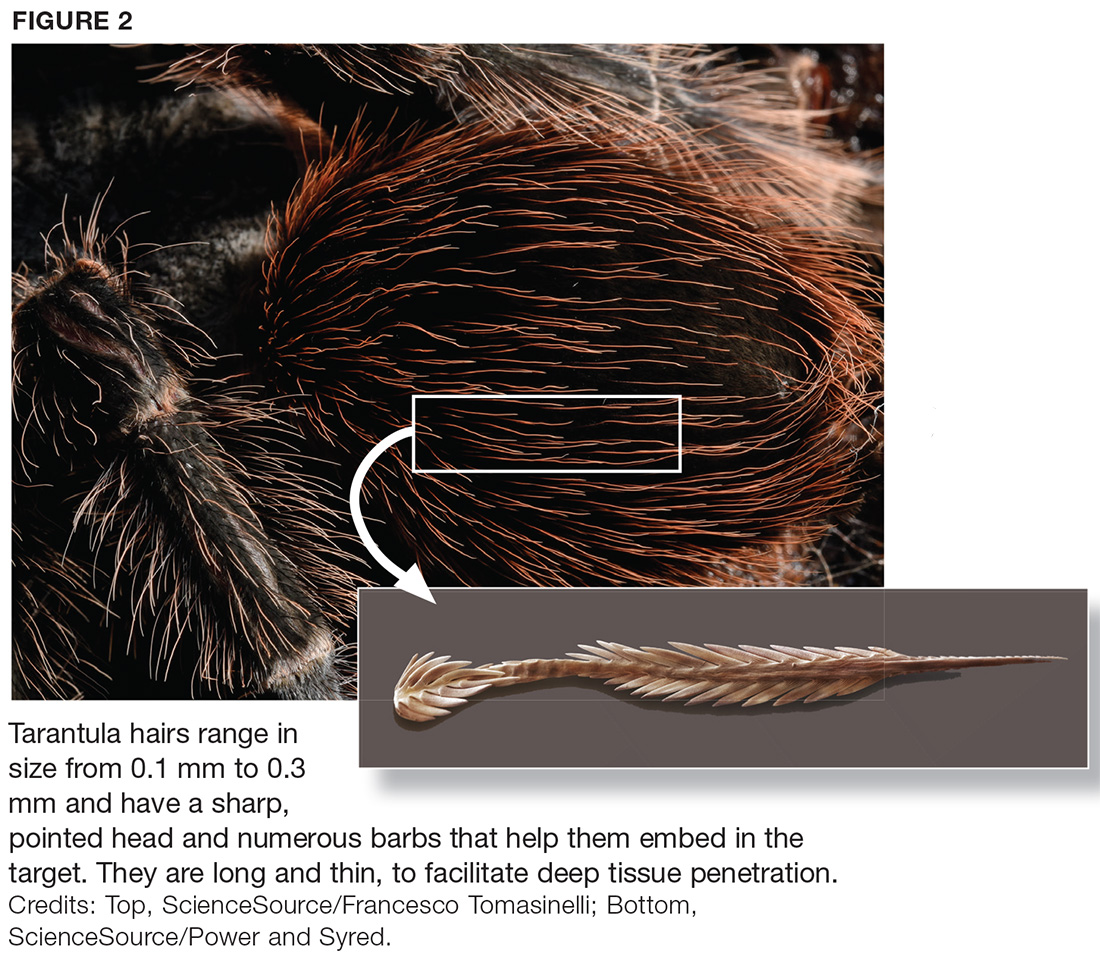

There are six types of urticating hairs. Each is attached to the spider’s cuticle by either a stalk (which represents the break-off region) or a socket.4 Tarantula hairs range in size from 0.1 mm to 0.3 mm and have a sharp, pointed head and numerous barbs, which help embed them in the target.5 They are long and thin, to facilitate deep tissue penetration, and can enter the eyes, lungs, or other body parts (see Figure 2).

Ocular injury from tarantula hairs commonly involves conjunctival injection, foreign body sensation, periorbital facial rash, photophobia, and tearing.3 When a tarantula’s cloud of barbed hairs is flicked into the eye and pierces the cornea, it can cause infection, irritation, scarring on the cornea, or vision loss. Eye movement or rubbing can cause the hairs—and their toxins—to migrate over time, traveling like an arrow (the tip and barbs resist backward movement) to the anterior chamber, lens, vitreous, and retina.6,7 This can cause corneal scars, cataracts, vitritis, or macular edema, and creates the possibility for acute or chronic conjunctivitis.7