IN THIS ARTICLE

- Types of shoulder dislocations

- Schematics of the shoulder with three types of dislocations

- Association with seizures

CASE A 59-year-old man with a remote history of seizures is transported to the emergency department (ED) by ambulance after a witnessed tonic-clonic seizure. At the time of arrival he is postictal and confused, but his vital signs are stable. A left eyebrow laceration indicating a possible fall is observed on physical exam, as is a left shoulder displacement with no obvious signs of neurovascular compromise. The patient is not currently taking anticonvulsant medication, stating that he has been “seizure free” for five years, and therefore chose to discontinue taking phenytoin against medical advice.

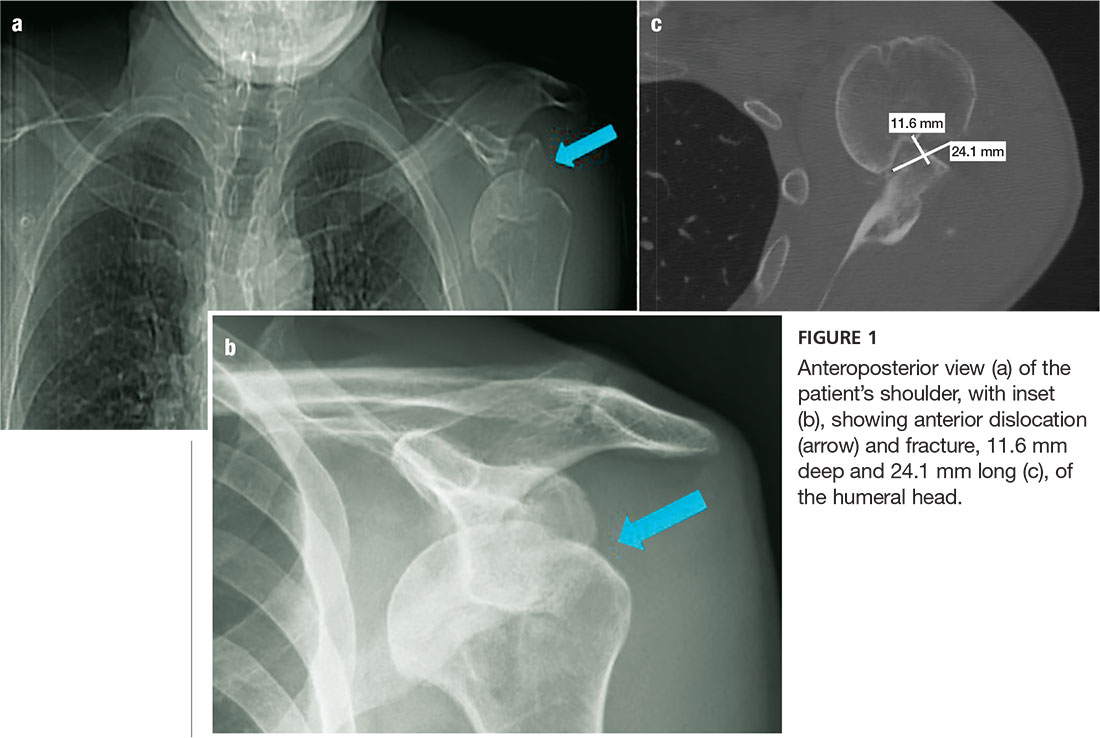

An anteroposterior (AP) bilateral shoulder x-ray is obtained in the ED (see Figures 1a and 1b). The image shows the humeral head to be anteriorly dislocated and reveals a large impaction fracture of the posterior superior humeral head. For a more detailed view of the fracture and to further assess any associated deformities, CT of the left shoulder is performed. The fracture has a depth of 11.6 mm and a length of 24.1 mm, with no additional pathology noted (see Figure 1c).

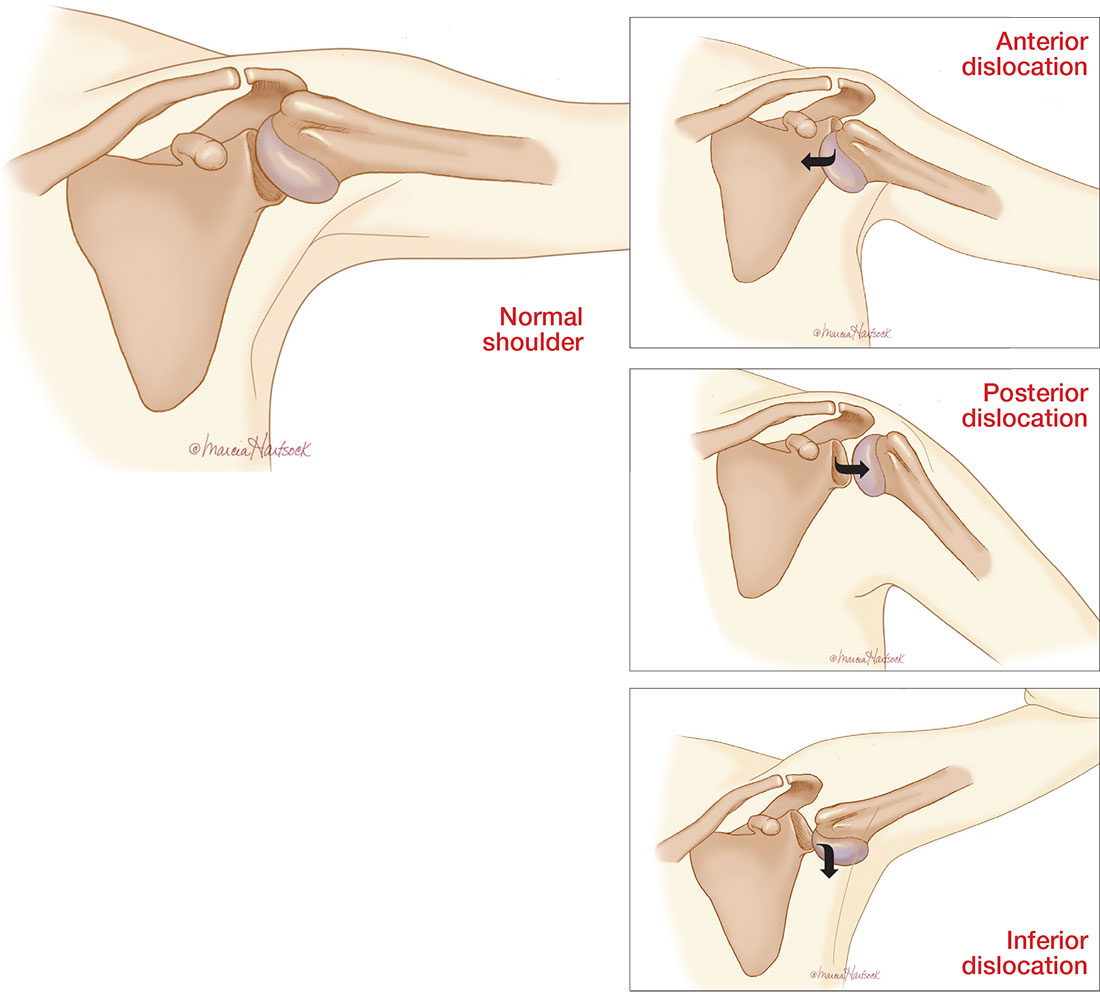

The shoulder is a large joint capable of moving in many directions and therefore is inherently unstable. The glenoid fossa is shallow, and stability of the joint is provided by both the fibrocartilaginous labrum and varying muscles of the rotator cuff. Because the shoulder joint is poorly supported, dislocations are not uncommon (see the illustrations).

The first step in evaluating a suspected shoulder dislocation is to order an AP radiographic view of the shoulder (known as the Grashey view). A transcapular view (known as the scapular “Y” view) is also sufficient.1 While diagnostic studies, such as CT or MRI arthrography, are excellent for evaluating the glenohumeral ligaments and labrum, they generally are not done in an acute setting.1 For patients who present to the ED, some would recommend taking a CT scan, especially if a posterior dislocation is suspected.2

The three types of shoulder dislocations include anterior, posterior, and inferior.

ANTERIOR

Anterior dislocations account for 95% of all presented cases of shoulder dislocation, making them the most common type.3 They may be caused by a fall on an outstretched arm, trauma to the posterior humerus, or—more frequently—trauma to the arm while it is extended, externally rotated, and abducted (eg, blocking a shot in basketball).

A patient with an anterior dislocation will enter the ED with a slightly abducted and externally rotated arm (see illustration) and will resist any movement by the examiner. Typically, the shoulder loses its rounded appearance, and in thin individuals, the acromion may be prominent. A detailed neurovascular examination of the arm must be performed.

Dislocation of the humerus in any direction may compromise the axillary nerve, artery, or both. The axillary nerve and artery run parallel to each other, beneath and in close proximity to the humeral head. The axillary artery is located upstream from the radial artery; compression of the artery may lead to a diminution or complete absence of the radial pulse and/or coolness of the hand.4 The axillary nerve is both a sensory and motor nerve. If injured, a 2- to 3-cm area over the lateral deltoid may have complete sensory loss, which can be tested for with a light touch and pinprick.5 The patient may also have difficulty abducting the arm, but limitations of movement are difficult to measure with a new dislocation and a patient in pain.4

Any patient presenting with an anterior shoulder dislocation should also be screened for two other potential abnormalities. Hill-Sachs lesion, which occurs in up to 40% of anterior dislocations and 90% of all dislocations, is a cortical depression occurring in the humeral head. Bankart lesions, which occur in less than 5% of all dislocations, are avulsed bone fragments that occur when there is a glenoid labrum disruption.6 Both can be seen on plain films, although Bankart lesions are best seen on CT.4

The combination of an anterior dislocation and a humeral fracture, as seen in this case, is rare.7

POSTERIOR

Posterior shoulder dislocations occur far less frequently than anterior dislocations, representing 2% to 5% of all shoulder dislocations.2 They often result from blows to the anterior portion of the shoulder (ie, motor vehicle accidents or sports-related collisions) or violent muscle contractions (eg, electrocution, electroconvulsive therapy, or seizures).

Unable to externally rotate the shoulder, patients with posterior dislocations present with the arm in adduction and internal rotation, making the coracoid process prominent (see illustration).8 This position is sometimes misdiagnosed as a “frozen shoulder.”2